Leadership or disruption? The Straits Times looks at how Donald Trump's coercive diplomacy kick-started the Singapore summit and caused various players to jostle for a piece of the action.

South Korea pins hopes of lasting peace on summit

For South Koreans, there is a surreal quality about the June 12 meeting between United States President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

There is clearly overwhelming support for the summit, yet it is something that many still find hard to believe is about to happen.

After all, the summit was nearly called off and just months before, President Trump and Mr Kim, who is Chairman of the State Affairs Commission, were issuing threats and counter-threats of nuclear annihilation. Now, Singapore is the focus of national attention as South Koreans pore over every twist and turn of the summit preparations, courtesy of the saturation coverage by the media here.

Traditionally, when it comes to North Korean issues, South Koreans tend to cleave along ideological lines, with the conservatives taking a jaundiced, wary view of the liberals' support for rapprochement with Pyongyang. But that is not the case now. The prospect of a lasting peace on the peninsula has meant near universal support for the June 12 meeting.

It has also boosted President Moon Jae In's popularity ratings to a record high. For Mr Moon, the success of the summit is vital, given the political capital he has expended on it, working single-mindedly to achieve a peace breakthrough since his inauguration in May last year.

Towards that end, he has set aside pressing domestic issues such as a sluggish economy and rising unemployment. As such, he cannot afford a failure or even a mediocre outcome from the summit.

A collapse in the talks would be a body blow to his presidency. A half-baked deal with unpredictable future contingencies is also fraught with risks - it would erode his support base and open him to attack from the opposition should the North Koreans backtrack on their commitments. It is very likely that Mr Moon will do his utmost to present the summit outcome in as positive a light as possible.

Ordinary South Koreans are indeed rooting for the Singapore summit to be successful. It is considered a historic opportunity to finally emerge from living for decades under the shadow of possible war.

If prosperity in recent years had blunted some of their fears, last year's confrontation between the US and North Korea provided a sobering reality check.

A common view here is that South Koreans have lived long enough under the threat of a northern onslaught since the end of the Korean War in 1953, and their children should not have to live in worse fear of a nuclear attack.

While the average citizen may not be familiar with the technical details of nuclear disarmament and verification, they do hope that the Singapore summit would lead to that, even if it is the first crucial step in a multi-step process. There is a distinction, though, between wholehearted support for success among the public and their assessment of what a grand settlement between the US and North Korea would mean for them in the longer term.

Two issues loom large: the possible dilution of US military protection and the cost of economic aid for North Korea.

Washington has pledged that neither the US-South Korea military alliance nor the presence of US troops in South Korea would be up for negotiation. But what concerns South Koreans is not so much the official status of the alliance as the gradual downsizing of the US troop presence over time as a consequence of a peace deal. As it is, Pyongyang wants US-South Korea military drills to be suspended in the spirit of the recent inter-Korea summit.

And then there is the matter of money. Massive economic aid packages for the North will likely follow a successful deal. Fortune magazine estimates the cost of North Korean denuclearisation at US$2 trillion (S$2.7 trillion), and South Korea is likely to bear a large share.

A question mark remains over how long the current mood of sacrifice in the name of peace will last.

But for now, all that matters for South Koreans is the promise of peace to come as Mr Trump and Mr Kim sit down for talks on June 12.

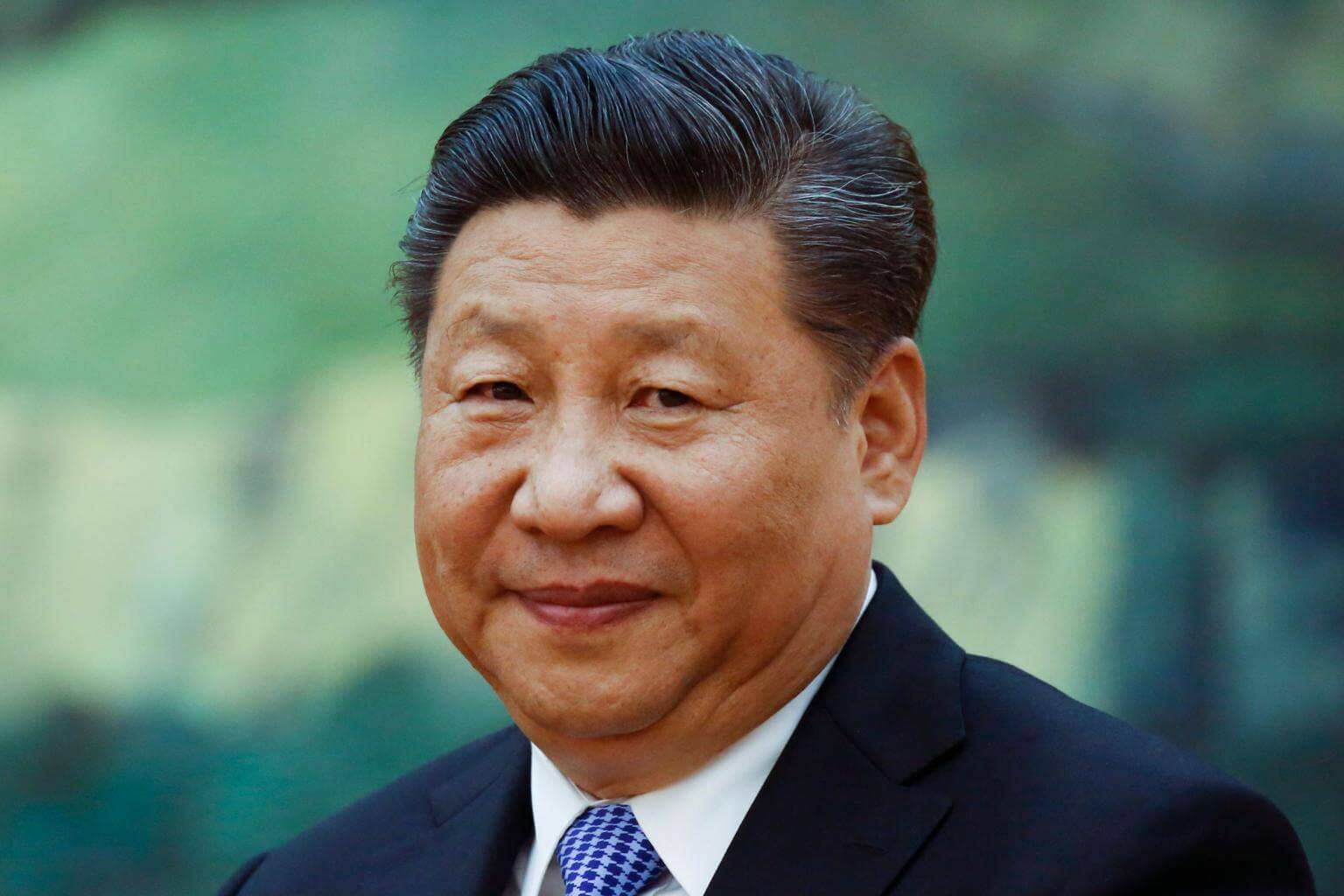

China wants positive outcome for security's sake

China wants to see a successful summit - whether substantive or symbolic - between United States President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

This is because a summit that goes well works in China's interest of having a stable and peaceful Korean peninsula and North-east Asia, Chinese analysts say.

But Beijing will also be watching the summit warily because its security interests are at stake. "Any positive outcome would be good news for China," said North Korea specialist Zhao Tong of the Carnegie-Tsinghua Centre for Global Policy.

If the two sides were to reach a comprehensive agreement on the nuclear issue, with North Korea making radical concessions and the US in turn promising to scale down its military exercises and reduce some of its military deployment, it would have a positive impact on China, he added.

Even if the two sides were to reach only a symbolic agreement that does not touch on the core dispute but simply preserves the status quo, with both sides making commitments to end hostilities and improve political relations, "that's fine too", he said. It would serve to de-escalate tensions in the Korean peninsula and reduce the risk of conflict at China's doorstep.

Failure at the summit would mean an escalation of tensions and China being wedged between a North Korea wanting more economic assistance and a US demanding a tightening of sanctions against Pyongyang.

However, Professor Su Hao of the China Foreign Affairs University did not think that the summit would fail to come up with a consensus between the US and North Korea on denuclearisation.

"We can expect that the two sides will achieve this result" of reaching an in-principle agreement on denuclearisation, he said, adding that China "will welcome this".

While Chinese analysts did not think China needed to be involved in the summit, there would be a certain amount of worry on the part of Beijing over what is discussed.

"China is in the room but not at the gaming table. It does not want to take part but would like to be able to see (what goes on at the table) and prevent its natural rights and interests from being encroached upon," said Professor Shi Yinhong of Renmin University, likening the summit to a round of gambling.

The anxiety stems from what Dr Zhao describes as China's deep distrust of the US and concerns about the deployment of increasingly advanced military assets in the region.

As tensions on the Korean peninsula rose over North Korea's nuclear and missile tests, the US last year deployed its advanced anti-ballistic missile system Thaad in South Korea despite vehement protests by China, which said the system compromised its security interests.

The US has also recently labelled China as a strategic rival and a revisionist power.

Still, Prof Su thought that even if South Korea's President Moon Jae In were to go to Singapore for a trilateral meeting right after the Trump-Kim summit to discuss the peace process, that would be acceptable to China.

The denuclearisation process would be linked to a peace process, he said, and there would be preparatory talks for the peace process in which Mr Moon as an intermediary should be involved. "We understand this and it's not a major issue," he said.

But China should not and cannot be absent from any talks to end the Korean War and any negotiation for a peace mechanism for the Korean peninsula, say Chinese analysts.

This is because China was a signatory of the armistice in 1953 that ended hostilities but not the Korean War.

Many analysts agree that Beijing would want to have a say in the peace process on the Korean peninsula as how the chips fall will have an impact on China's security interests.

Japan eyes direct talks amid focus on abductions

Japan has been a vocal advocate of the "maximum pressure" campaign against North Korea, eschewing talks and insisting that "dialogue for the sake of dialogue is meaningless".

But with the United States, a long-time security ally, going into an unprecedented summit with the North, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe realises he has to speak directly with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un for any hope of resolving the longstanding issue of the kidnapping of Japanese citizens by agents of Pyongyang in the 1970s and 1980s.The issue was a clear priority for Mr Abe when he met privately with Mr Donald Trump at the White House on Thursday, the seventh meeting between the two leaders.

"Japan, ourselves, must talk directly with North Korea," Mr Abe told reporters as he stood next to Mr Trump. "I hope we will be able to realise a summit meeting which would lead to a solution of the problems."

Mr Trump also referred to the abduction issue after the talks with the Japanese prime minister.

He said: "It was pre-eminent in our conversations. He talked about it long and hard and passionately. And I will follow his wishes, and we will be discussing that with North Korea, absolutely." This is heartening news for Japan, which has been anxious that its interests were being disregarded amid the fast-moving developments in the lead-up to the Trump-Kim summit.

Yet this also comes as Japan has long been wary of trusting North Korea and has often looked to historical precedents to warn against Pyongyang's charm offensive.

Japan has often followed the US lead on North Korea policy but has been caught off-guard at least twice - first, with Mr Trump agreeing to meet Mr Kim, and then on June 1, when he said he did not want to use the phrase "maximum pressure" any more.

Mr Trump has now promised Mr Abe that he would raise the following issues:

•Complete, verifiable, irreversible denuclearisation (CVID) and dismantling the North's nuclear stockpile and missile arsenal, which must include both intercontinental ballistic missiles that can strike the US mainland, and the short-and intermediate-range missiles that put Japan in the North's cross hairs.

•The abduction issue.

Japan's strident campaign against North Korea has led to pushback from other stakeholders, including South Korea, and many Japanese analysts concur that Tokyo has to dial down the rhetoric and pursue talks with Pyongyang. While sanctions have not been relaxed, Tokyo is concerned that an easing of the hawkish stance will encourage an easing of sanctions.

Dr Katsuhisa Furukawa, a former UN expert monitoring sanctions against the North, said: "Japan's posture looks as if it is only pursuing a hard-line hawkish approach, without any diplomatic considerations."

Keio University security expert Ken Jimbo said that while Japan should continue to impose sanctions until solid steps are taken towards CVID, it should also be "more proactive" in contributing to a multilateral approach to pursue the North's denuclearisation.

On the abductions, former top diplomat Hitoshi Tanaka, who was involved in Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's visit to Pyongyang in 2002 and 2004, said Japan "should not be asking another sovereign nation to help it resolve its problems".

Tokyo officially recognises 17 abduction cases, with five victims returned in 2002 after Mr Koizumi's talks with then North Korean leader Kim Jong Il. Japan wants proper accounting on the remaining 12 victims. But Pyongyang, asserting that the matter has long been resolved, said eight had died and the other four never entered the country.

Associate Professor Atsuhito Isozaki, a scholar on North Korean issues at Keio University, wondered if Japan might have lost the leverage it once had on Pyongyang.

"Japan's position as an economic power in East Asia is not as large as it was 16 years ago," he said.

Nonetheless, his colleague, Dr Yasushi Watanabe, believed that it might only be a matter of months before Mr Abe meets Mr Kim.

Russia has few cards, but keen to show it's key actor

Russia is determined to remind the world that, despite its negligible involvement in the diplomatic preparations for the Trump-Kim summit in Singapore, it remains a key strategic actor on the Korean peninsula.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has recently returned from a hastily arranged visit to Pyongyang, and Moscow officials are delighted that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, officially Chairman of the State Affairs Commission, has agreed to visit Russia later this year.

Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that the Russians will succeed in wedging themselves into any disarmament process which may be agreed for the Korean peninsula. For Moscow has few diplomatic cards to play in this crisis.

The Soviet Union used to be North Korea's closest ally. The North's political system is essentially a copy of the Soviet one and even when relations between the USSR and China were at their worst in the 1960s and 1970s, Pyongyang maintained cordial relations with both Beijing and Moscow, and benefited from Soviet-made weapons which poured across its short border with Russia.

Matters changed, however, when the Soviet Union collapsed, and Russia took a greater interest in lucrative investment deals with Japan and South Korea, rather than with impoverished North Korea.

And although Russian interest in the peninsula increased as North Korea's nuclear programme came to international attention after Pyongyang's first nuclear test in 2006, Moscow always deferred to China on such matters, partly because the Chinese are clearly the dominant power in the region but also because China's key strategic objectives in the crisis - to prevent a greater US military involvement in the peninsula and avoid Korean unification - are also Russia's key interests.

For years, therefore, Russia attended the Six-Party Talks on Korea but said absolutely nothing. It was merely content to have a seat at what was considered an exclusive security club.

Still, Russian President Vladimir Putin's determination to make Russia an indispensable power in the handling of any international crisis, noticeable especially after Russia's military involvement in Ukraine in 2014 and the Russian deployment of troops in Syria the year after, has had an impact on the Koreas as well.

Moscow touted the idea of building a railway link across the shared border to connect both Koreas and terminate in Busan, giving Russia access to an alternative Pacific port to its own Vladivostok, which freezes for many months in the bitter Siberian winter.

Mr Putin also proposed a gas pipeline through North Korea and down to the southern tip of the Korean peninsula, tying both Koreas to Russia's energy grid.

Nothing came out of these proposals, however, partly because they are hugely expensive and partly because they are only useful after - and not before - the nuclear crisis is addressed. Furthermore, Mr Putin quickly realised that playing a unique role on the Korean peninsula may annoy the Chinese, something that won't be in Moscow's interest.

As a result, Russia's current diplomatic efforts are more about ensuring that it is not forgotten, rather than about promoting any agenda.

On his recent trip to Pyongyang, Mr Lavrov urged the US to incentivise North Korea into a deal by lifting some of the United Nations-imposed sanctions soon after the Singapore summit.

"As we start discussions on how to resolve the nuclear problem on the Korean peninsula, it is understood that the solution cannot be comprehensive without the lifting of sanctions," he said in a clear attempt at Russian diplomacy.

The Russians are also delighted that Mr Kim has agreed to attend an economic forum in September in Vladivostok.

But ultimately, this is mostly window-dressing. Neither the Chinese nor the Americans nor the two Koreas have an interest in snubbing Russia, so they all take a polite interest in what Moscow has to say. But none has too much time to spend on Russian proposals either.