SINGAPORE - International Week of the Deaf is celebrated in the last full week of September.

For Mrs Noor Aini, 36, whose son Muhammad Zahin Feroz Khan was born with hearing loss in both ears, she has reason to be optimistic about his future.

"We had it very tough during the first four years of his life," says the administrative executive.

While the use of hearing aids and speech therapy enhanced his listening and speech skills, "he used to have a lot of meltdowns due to the frustration of not being able to communicate to a fuller extent", she adds.

"Learning sign language was a game changer," says Mrs Noor Aini, who enrolled Zahin in the Fei Yue Early Intervention Centre For Children when he was four.

A year ago, he joined The Little Hands bilingual-bicultural programme. He is one of 11 children in the communication programme run by the Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) in Mountbatten Road, for children aged 2½ to seven.

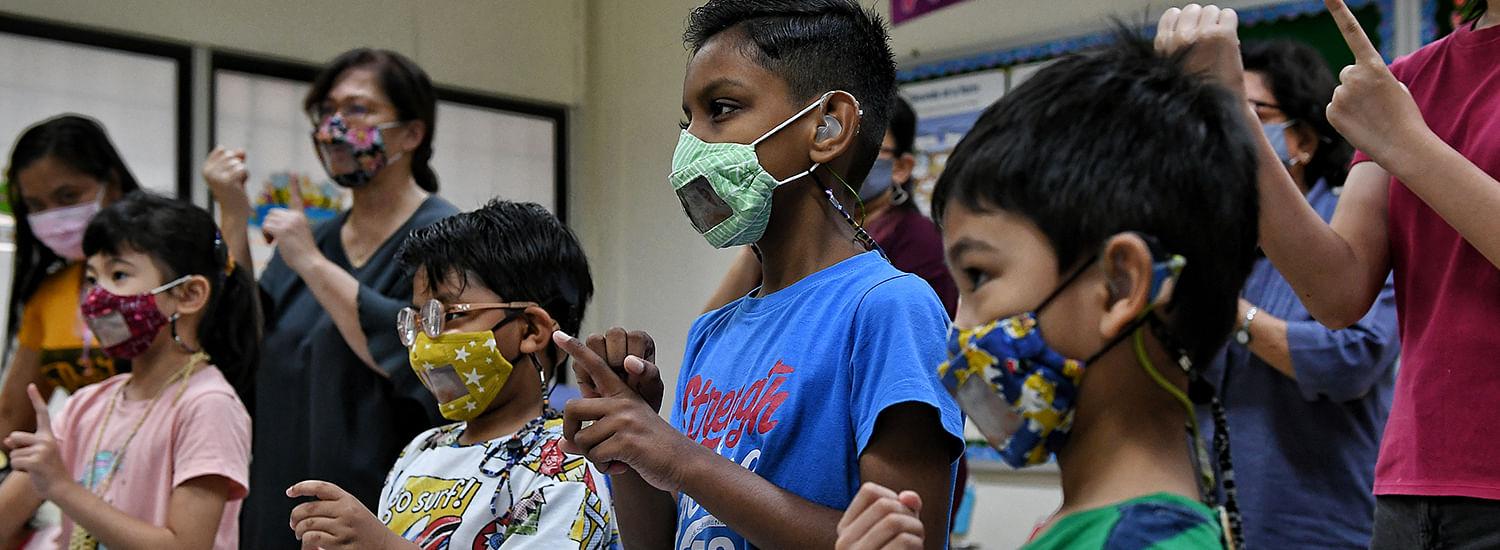

The participants, who have varying degrees and types of hearing loss, attend the sessions five days a week, from 9am to 12.30pm.

At the start of the day, they sign the Singapore pledge with their teachers. Those who are verbal are encouraged to speak as well while signing.

By 9.30am, Zahin is a "doctor" in an enactment of a scene in a clinic, as he practises communicating with "patients" and "nurses" played by his classmates.

Now seven, Zahin is happy, confident and can switch between sign language and spoken English.

Little Hands strongly advocates teaching sign language to deaf children from a young age.

The "bilingualism" part of the programme refers to the use of both sign language and speech, if the child is able to.

Ms Barbara D'Cotta, training manager and coordinator who established the programme, says: "We want to dispel the notion that voice training is omitted when children learn signing."

She used to teach at Mayflower Primary School, Singapore's designated school for deaf pupils. Specialised teachers from SADeaf co-teach the mainstream curriculum to deaf pupils, alongside hearing ones.

It was there that she noticed a large language gap in children entering primary school.

"They lacked the social and academic language to access the curriculum. This included reading and writing, and also sign language which is used during co-taught classes," she says.

She started Little Hands in 2018, which is completely funded by SADeaf.

Besides learning the Singapore Sign Language (sgSL) used by the deaf community here, art, maths and English (grammar and vocabulary), the children also go through role-playing exercises where they practise interaction in different scenarios.

"This gives them confidence in different social settings where they may or may not be the only one who is deaf," says Ms D'Cotta.

This is the "bicultural" element - exposing the children to both deaf culture and situations where they have to interact with hearing persons.

SADeaf deputy director Alvan Yap says: "Any language is important from the time they are born, and for many deaf kids, sign language is the most accessible. The most important thing is to make language accessible to children, and to build their cognitive senses."

"The common misconception is that speech is the only form of language, but sign is a visual language which can be the bridge of communication before spoken language is learnt," he adds.

Ms D'Cotta says: "I hope more parents will be aware of the need for their children to use another mode of communication (sign language) which will help them build cognitively and assimilate into mainstream curriculum."