"Do you believe in the concept of a safety net?" the host of BBC's Hard Talk Stephen Sackur asked then Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam during a live one-to-one in 2015.

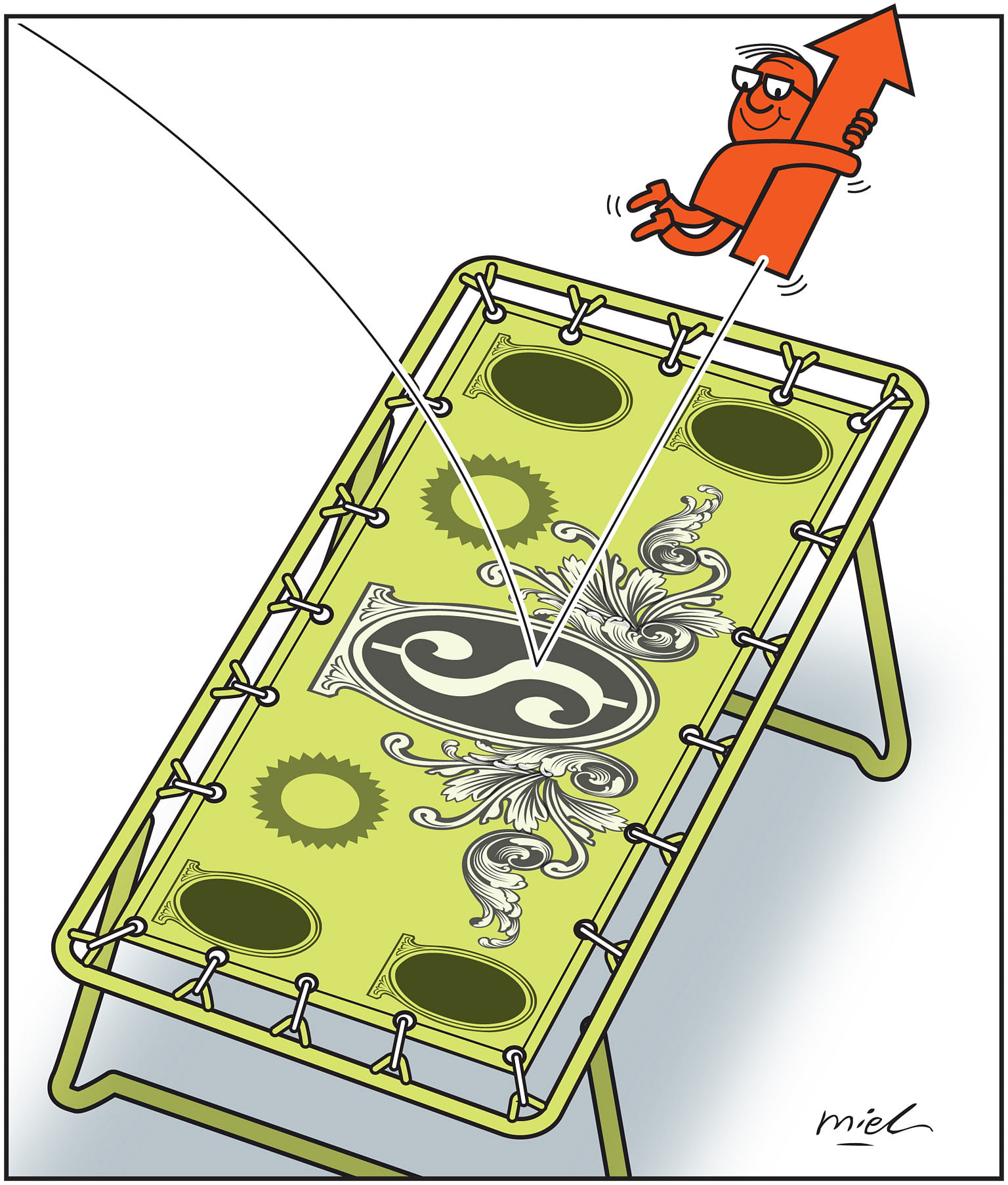

"I believe in the notion of a trampoline," replied Mr Tharman, in the best soundbite of the interview. In this extraordinary pandemic-induced recession, trampolines are what we need.

The recession is spreading across the economy, impacting thousands of companies and potentially millions of workers. Despite the Government's massive fiscal support, bankruptcies and lay-offs will be inevitable. Estimates of how many workers are likely to lose their jobs vary, but in the worst case - which is what we should prepare for - the number could run up to as high as 200,000 this year, according to economists from Maybank. This would be more than six times the previous high of 32,800 lay-offs during the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998.

With a "V-shaped" recovery unlikely, many businesses may have to go into hibernation for extended periods and thousands of those laid off could be out of work for several months.

The Government could respond by continuing with new fiscal measures periodically, as it has done four times in the last three months, depending on how the situation evolves.

Or it could, once and for all, provide safety nets for both individuals and companies that are more durable.

The end goal should be twofold: first, to relieve people of the anxiety that they may not have enough income to support themselves and their families through this crisis, especially if they are laid off - which could happen at any time; and second, to ensure that as many companies as possible are still alive and viable after the crisis passes, so that the economy can restart quickly.

Various economists have offered constructive ideas on what kind of safety nets might be appropriate. Here are some of them: TIME FOR UBI For individuals and families, Nominated MP Walter Theseira, who is an associate professor of economics at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, proposed a universal basic income (UBI) scheme in Parliament on April 7. The UBI is not a new idea and is being advocated by increasing numbers of academics, politicians and even Pope Francis.

But Associate Professor Theseira, in a joint study with Dr Ong Qiyan, deputy director of research at the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Social Service Research Centre, proposes a version that might be relevant for Singapore.

Under the proposal, called the Majulah Universal Basic Income (Mubi) Scheme, all Singaporeans, including children and retirees, will get $110 a week for 12 weeks. This income will be taxable, which means the cost of the scheme can be recouped from future taxes.

In essence, Prof Theseira suggests that the scheme "will distribute money from the future, when the economy and jobs are expected to recover, to the present, when many Singaporeans are facing immediate cash flow problems as they lose jobs or face sharp reductions in income".

To raise the $4.62 billion that the scheme would cost, he proposes a temporary personal income tax increase of 4.25 per cent for those earning more than $20,000 annually. By his calculations, this would mean that high-income earners would end up paying back more in taxes than they earned from the Mubi scheme.

The idea has many merits. First, it is universal and extended to all citizens. This is especially appropriate during this particular crisis, when it will be hard to predict which categories of workers will be laid off or suffer income losses - they could also include white-collar professionals.

So, the scheme would fill a vital gap in the absence of universal unemployment insurance.

Second, unlike existing schemes such as the Workfare Income Supplement, it is automatic - requiring no application or eligibility criteria.

Third, it has a redistributive element - the rich will pay more than they receive and the poor will pay less.

Fourth, it can enable the Government to eliminate or reduce some other temporary benefits that it provides - such as the income relief scheme for self-employed workers and various one-off payments and top-ups - which would yield some savings.

Most importantly, it would provide a predictable and assured source of income that would relieve families of financial stress and ensure a minimum level of demand in the economy that would help all operating businesses.

It would also allow those who are laid off some time to search for jobs for which they are qualified, rather than being forced to take the first available job out of desperation - which would minimise job mismatches. It is unlikely to erode incentives to work - the available evidence on UBI suggests that this does not happen. Besides, the problem we will face during this crisis is not of people trying to avoid work, but of people wanting to work, but who can't.

Prof Theseira has pegged the amount of income support under Mubi at a subsistence level. It could be increased - say, to $150 per week per person - and its duration extended, which would require a higher temporary tax rate in the future. But in terms of its structure, the scheme seems sound and timely. It might have been a radical idea in the past. But in the present context, it is not. Those who object to a temporary UBI during this crisis should ask themselves - what is the alternative?

HELPING COMPANIES

What can be done for companies?

In its budgets so far, the Government has extended subsidies on wage costs of at least 25 per cent on salaries up to $4,600 per month till the end of the year - which has probably already prevented many bankruptcies and lay-offs - as well as a patchwork of tax reliefs and loan schemes, mainly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). But, especially for companies whose revenues have collapsed, these measures are unlikely to be sufficient to prevent bankruptcies or lay-offs.

Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman from the University of California at Berkeley have proposed that, at least for companies that were profitable before the crisis, the government should act as a "payer of last resort", by helping such companies pay essential maintenance costs - which may include rent, utilities and interest.

For companies under partial shutdown - for example, restaurants that cannot serve customers on site, but are open for takeaways and deliveries - the Government can provide half, or some proportion, of maintenance costs. Ideally the support should be provided directly by the Government rather than routed conditionally through the banks, because otherwise the main beneficiaries would be companies with the best banking relationships.

Companies that receive such support should be encouraged to avoid laying off their workers, but putting them on no-pay leave until the situation improves. So even if they are dormant during the crisis, the companies would still be alive and viable when it passes and can resume normal business.

Meanwhile, the workers would have been supported by the UBI, if not by their companies, and there would be no need for rehiring. The Government could recoup at least some of its assistance through a corporate tax surcharge in the future.

A different, and innovative, proposal to help companies comes from finance professors Joseph Cherian of the NUS Business School and Marti Subrahmanyam of the Stern School of Business at New York University.

In an article in The Business Times last month, they pointed out that while loans - which comprise a key element of existing government support schemes - might help companies stay afloat in the short run, the burden of debt repayment could prove onerous after the crisis is over, especially for SMEs. Professors Cherian and Subrahmanyam suggest that an infusion of equity finance may be a more promising solution. In essence, they propose that at least those companies that were profitable before the Covid-19 crisis should get equity financing from a government entity - which could be a special purpose vehicle (SPV).

The SPV would take partial ownership of a company and later get dividends in the form of a share of corporate taxes for a number of years, with the company retaining the right to buy back the equity in the future at a reasonable valuation. This equity infusion would help companies - which might otherwise go bust - to not only continue operations, but also upgrade, innovate and internationalise.

PROTECTING THE HOUSING MARKET

Another potential hazard arising from the Covid-19 crisis is stress in the housing market. This has happened in past recessions.

Fortunately, Singapore has avoided a housing market bubble in recent years, thanks to multiple rounds of property cooling measures since 2009. However, in a deep recession, housing prices are always vulnerable: As lay-offs increase and the recession deepens, housing prices could start to slide. This can be dangerous to people's financial health.

The majority of Singaporeans' net worth is held in the form of home equity. If property prices fall beyond a point, some highly indebted home owners could become "underwater" on their mortgages. Their equity would be wiped out, but their level of debt would remain high. If they were to sell their home, they would have to pay the bank the difference between the outstanding mortgage and the sale price.

Some, who might be laid off, might have no option but to allow the bank to foreclose. This is what happened in the United States during the 2008 financial crisis.

Banks ended up selling millions of properties at discounted prices, driving all property values down, hurting even those home owners who were not heavily indebted and worsening the recession.

Economists Atif Mian of Princeton University and Amir Sufi of the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business proposed an innovative idea to prevent such massive housing market distress and wealth destruction.

They suggested a "shared responsibility mortgage" (SRM) where the risks arising from a housing market correction are shared between borrowers and lenders. Under existing mortgages, if a home buyer makes a 20 per cent down payment and property prices correct 20 per cent, the home buyer loses all his equity, but the bank loses nothing - which is bad for not only the home buyer but also the economy.

Under the SRM, if property prices fall by 20 per cent, mortgage payments would also fall by 20 per cent. The tenure of the mortgage remains unchanged, which means the proposal essentially amounts to an automatic write-down of principal for a temporary period during the crisis.

To compensate banks for providing this downside protection, they will get 5 per cent of any future capital gains when the homes are sold. With a stable flow of 5 per cent of capital gains on their mortgage portfolios, banks would be more than compensated for the additional risk they take. Home owners' wealth would be better protected and mass foreclosures prevented. The SRM, which would be temporary, requires no more than a simple rewriting of mortgage contracts.

These are some of the unorthodox ideas that we should consider if we are to find the trampolines we need.