"It doesn't quite matter to me now what time I go home," says Professor Leo Yee Sin, executive director of the National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID). "Because I continue to work at home."

She works not only long hours, but also seven days a week since the Covid-19 outbreak hit Singapore.

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, her day starts with a two-hour meeting at 8am - so she needs to be in by 7.30am to get ready and to catch up with things that had occurred overnight.

These meetings look at the situation here and globally. The 20 to 30 people involved discuss - remotely - how Covid-19 affects different patients, the perspective from the laboratories and the sort of care patients need.

Aside from seeing more than half the Covid-19 patients here, the NCID, as the dedicated specialist institute for infectious diseases, also has to provide clinical leadership for the country.

Says Prof Leo: "In addition to providing care, we have to be able to analyse the cases and understand the disease characteristics.

"We give evidence-based advice to the Ministry of Health (MOH), which can then come up with policy that can translate into action."

Some key findings, after Singapore has had more than 17,000 people infected, include confirming that older people tend to get more severely ill.

The MOH says that as of April 16, "among the confirmed cases aged below 50 years old, 0.2 per cent required ICU (intensive) care, compared with 11 per cent for those aged 50 years and above".

CRUCIAL MARKERS

The experts have also identified predictive markers from chest X-rays and blood tests, and are now able to identify patients who are likely to suffer no more than a mild illness, and those who might face more serious illness.

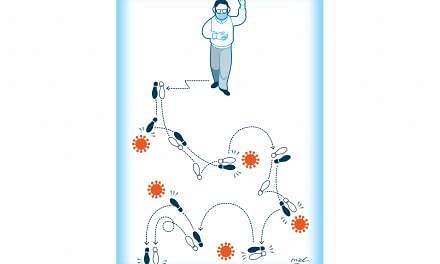

As a result, a young healthy patient whose swab tests positive at a polyclinic is no longer sent to a hospital but straight to a community setting.

Today, only patients who are likely to become very ill are housed in a public general hospital or at the NCID.

Those in the mid-range would be sent to the handful of community hospitals treating Covid-19 patients. The 317-bed Bright Vision Hospital is now dedicated to recovering Covid-19 patients. Yishun, Jurong and St Andrew's community hospitals have each set aside a few wards for Covid-19 patients.

Prof Leo says not all nine community hospitals are suitable, as some still have other patients. These hospitals also have to be "very secure" if they are treating patients infected with the coronavirus.

She stresses that such pre-admission clinical assessments are continuously evolving.

Meanwhile, the 330-bed NCID that was opened just last year, with provisions for expansion during an emergency to accommodate more than 500 beds, is running very full.

"Every corner is being used," says Prof Leo. "We're very full, hovering about 90 per cent occupancy. Every single ward and every single room is being used."

At maximum capacity, with two to three beds per cubicle, the centre can accommodate "an absolute maximum 586 patients", she says.

But this is not possible. First, patients who are only suspect cases have to be kept isolated. Only confirmed patients can be roomed together. So the NCID can take in only slightly more than 500 patients at any one time.

Furthermore, the centre discharges, or moves to other facilities, more than 100 patients a day. Those wards have to undergo a thorough cleaning that takes about two hours. This is on top of the daily cleaning of "high touch" areas in the wards.

Prof Leo, who is one of Singapore's top infectious disease experts and led Singapore through another coronavirus outbreak, the severe acute respiratory syndrome or Sars, now has little time to practise her vocation.

As the head of NCID, she participates in patient care only outside of the wards, by trying to understand the disease and identifying the big picture.

Her time is now largely spent on administrative tasks, she says, and include worrying about "cranky" automatic doors acting up and electric power trips - both of which have happened this year, but fortunately did not affect patient care and were quickly fixed.

Anything in use has to be maintained, she says. Her job includes ensuring that when there are hiccups to the system, follow-up action is taken as quickly as possible.

Overseeing the care of patients, finding out as much as possible about the disease, and making sure the infrastructure works smoothly are both physically and mentally stressful, she says, "with a lot of work and little rest time".

She also has to take care of her staff and make sure they take precautions outside of work. She says: "A lot of times people forget. They think they are at risk when at work and there is no risk when going out."

They need to completely change their mindset, she says. In the wards, they are in no danger with personal protective equipment. She constantly reminds them that they need to maintain social distancing and not go out in a big group when they buy lunch.

She adds that the healthcare workers are very good at giving one another social support. Her staff even sees that she gets breakfast and lunch, which she takes on the run.

At home her family is also very understanding. Her three children are grown up, although two still live at home with her and her husband.

She tries to have dinner with them, and manages to do so about three times a week, although the dinners "are a bit rushed", she says, as there are usually night-time conference discussions.

Life like this will go on for quite a long time, says Prof Leo. Her greatest worry is whether people here are resilient enough and willing to do their part in beating the viral spread.

And her greatest wish: "For us to be ahead of the virus. Now we are behind. Until we know the enemy very well, we're still on the learning curve."

But she is confident: "We will get through it, that I'm very sure. As humans, somehow, we will find a way. The issue here is how long (it will take)."