PARIS (AFP, REUTERS) - Vast tracts of pristine rainforest on three continents went up in smoke last year, with an area roughly the size of Switzerland cut down or burned, much of it to make way for cattle and commercial crops, researchers said on Tuesday (June 2).

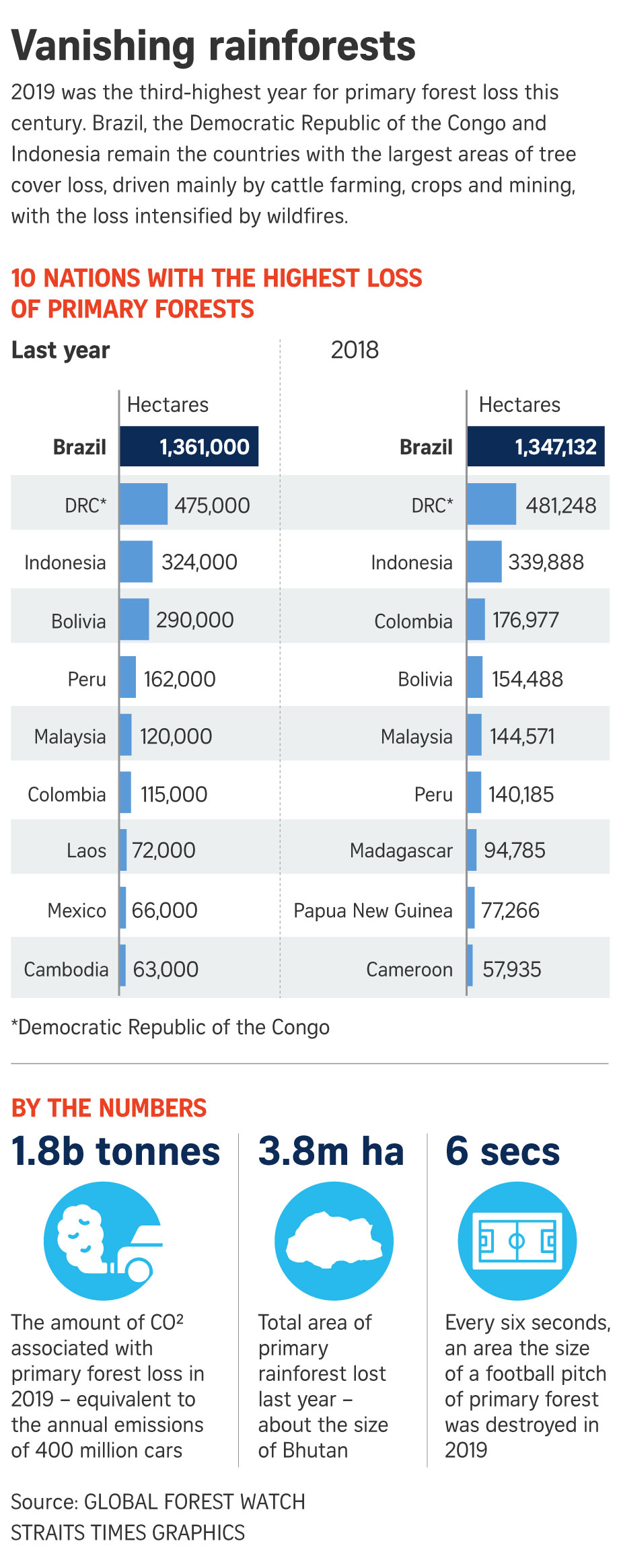

Brazil accounted for more than a third of the loss, with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia a distant second and third, Global Forest Watch said in its annual report, based on satellite data.

The 38,000 sq km destroyed in 2019 - equivalent to a football pitch of old-growth trees every six seconds - made it the third most devastating year for primary forests since the scientists began tracking their decline two decades ago.

"We are concerned that the rate of loss is so high despite all the efforts of different countries and companies to reduce deforestation," lead researcher Mikaela Weisse, Global Forest Watch project manager at the World Resources Institute (WRI), told Agence France-Presse.

The total area of tropical forest levelled by fire and bulldozers worldwide last year was in fact three times higher - but virgin rainforests, as they were once known, are especially precious.

Undisturbed by modern development, they harbour the richest diversity of wildlife on earth, and keep huge stores of carbon locked in their woody mass.

When set ablaze, that carbon escapes into the atmosphere as planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO2), the main greenhouse gas.

"It will take decades or even centuries for these forests to get back to their original state" - assuming, of course, that the land they once covered is left undisturbed, Ms Weisse said.

The forest fires that engulfed parts of Brazil last year made front-page news as the climate crisis loomed large in the public eye.

But they were not the main cause of Brazil's loss of primary forest, the data showed.

Satellite images revealed many new "hot spots" of forest destruction. In the state of Para, for example, these fire-ravaged zones corresponded to reports of illegal land grabs inside the Trincheira/Bacaja indigenous reserve.

RARE BRIGHT SPOT

And that was before President Jair Bolsonaro's government proposed legislation that would relax restrictions within these nominally protected regions on commercial mining, oil and gas extraction, and large-scale agriculture - all of which could make such incursions even more common.

Ms Frances Seymour, a senior fellow at WRI, said this is not only unjust for the people who have lived in Brazil's rainforests for uncounted generations, but also bad management.

"We know that deforestation is lower in indigenous territories," she said.

"A mounting body of evidence suggests that legal recognition of indigenous land rights provides greater forest protection."

The pandemic could also make things worse, not just in Brazil - which has been hit especially hard by Covid-19 - but anywhere it saps the already anaemic enforcement capacities of tropical forest nations.

"Anecdotal reports of increased levels of illegal logging, mining, poaching and other forest crimes are streaming in from all over the world," Ms Seymour noted.

Neighbouring Bolivia saw unprecedented tree-cover loss in 2019 - 80 per cent higher than any year on record - due to fires, both within primary forests and surrounding woodlands.

Soya production and cattle ranching were the two main drivers.

Indonesia, meanwhile, showed a 5 per cent drop in the area of forest - 3,240 sq km - destroyed in 2019, the third consecutive year of decline, and nearly three times less than in the peak year 2016.

"Indonesia has been one of the few bright spots in the global data on tropical deforestation over the last few years," Ms Seymour and two colleagues wrote in a recent blog post.

Tougher law enforcement to prevent forest fires and land clearing, and bans on forest-clearing and new oil-palm concessions all helped, said Mr Arief Wijaya, forests and climate manager at WRI Indonesia.

"I would (now) like to see the government not only trying to reduce deforestation but reverse deforestation," Mr Wijaya said.

As the South-east Asian nation battles the coronavirus pandemic, it is important that funds set aside for forest protection and restoration are not reallocated to help the wider economy and healthcare system, he added.

Tropical ecosystems are vulnerable to both climate change and extractive exploitation.

A study in March calculated that the Amazon rainforest is nearing a threshold of deforestation which, once crossed, would see it morph into arid savannah within half a century.

The other countries with the most severe losses of primary forests in 2019 were Peru (1,620 sq km), Malaysia (1,200 sq km), and Colombia (1,150 sq km), followed by Laos, Mexico and Cambodia, all with less than 800 sq km.

In total, the tropics lost 11.9 million hectares of tree cover - which includes all natural forests and tree plantations - in 2019, according to the GFW data.

Outside the tropics, huge wildfires also took a toll.

Australia experienced a 560 per cent jump in tree cover loss from 2018, driven by unprecedented bush fires, making it easily the country's worst year on record.

And the true impact of Australia's fires on tree cover loss is likely to be worse, WRI said, because the burning that continued into 2020 was not captured in the data.

Over six months or so, the fires tore through millions of hectares of forests and farmland parched by record-low rainfall and record temperatures, with climate change playing a major role in creating the deadly conditions.