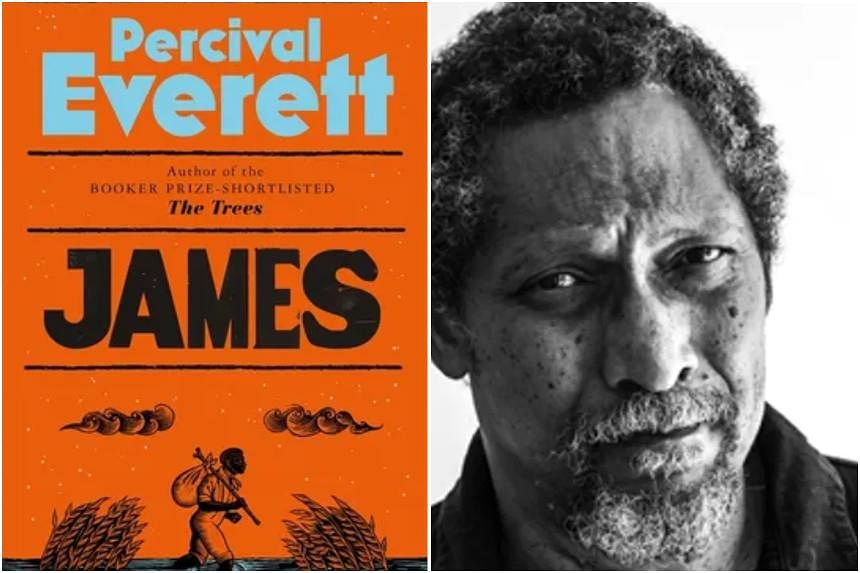

James

By Percival Everett

Fiction/Mantle/Hardcover/320 pages/$30.27/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3UJWLQ5)

4 stars

As racial issues flare and threaten to polarise the United States time and again, the razor-sharp societal critiques by American writer Percival Everett – masked as comical parody – has gained importance.

The 67-year-old has gained a following by addressing black issues audaciously and with beguiling humour.

In his latest work, he follows the adventure of runaway slave Jim and his brave young companion Huckleberry Finn in an antebellum American South, where slaves have no rights.

If this plotline sounds familiar, it is because Everett has riffed off the 1884 Mark Twain classic, The Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn, and rewritten it from the slave’s perspective.

In Twain’s novel, Jim was practically silenced as a simpleton slave in what was a coming-of-age story for 14-year-old Huck, who comes to terms with his friendship with his enslaved companion despite the learnt societal prejudice.

Jim becomes whole as Everett gives him not just a voice, but also literacy: “My interest is in how these marks that I am scratching on this page can mean anything at all. If they can have meaning, then life can have meaning, and I can have meaning.”

The conceit is brilliantly straightforward, and readers will still enjoy reading James even if they are unfamiliar with Twain’s novel.

While the classic has often been regarded as a touchstone of American literature, it has been riven with controversy in recent decades. The book has either been banned in schools for its liberal use of the offensive N-word – with more than 200 instances in the original text – or censored with the slur entirely scrubbed out.

But to not use the slur in a novel set in pre-civil war America would be anachronistic, and Everett, who is black, does not shy away from the racially charged slur that was once everyday parlance.

He pulls no punches, as in his previous works like Erasure (2001), which was adapted into the Oscar-winning American Fiction (2023). In that film, an exasperated black novelist manages to hit big time only when he writes an outlandish satire of “black literature”, which fits into the cookie-cutter mould of what society sees black writers as capable of.

Or The Trees (2021) – for which Everett was shortlisted for the Booker Prize – in which he borrows a lynching incident that was one of the darkest moments of US history, to caricature redneck America.

In James, much of the scaffolding remains even as Everett upends the classic.

Like in the original, Huckleberry Finn or “Huck” fakes his death to flee from his alcoholic and abusive father. Jim – in effect a lowbrow disguise to mask the real “James” – overhears that he is to be sold to a new owner and separated from his wife and daughter, and decides to flee.

Thus begins the unlikely pair’s odyssey along the choppy waters of the Mississippi River.

They would get separated on their journey, though Everett’s retelling fills in the gaps from Jim’s perspectives. They also encounter other Twain characters, such as the bungling, shameless con-artists King and Duke.

Jim is a man with many secrets, many of them to do with language and identity.

He is both literate and literary, to the point that he has philosophical debates in his dreams with the likes of philosophers Voltaire and John Locke. Jim aspires to write a memoir, for which he craves a pencil and a notebook.

In front of their white masters, the blacks are mindful not to break character and communicate in a lowbrow dialect. They otherwise code-switch, as Jim notes: “What would they do to a slave who knew what a hypotenuse was, what irony meant, how retribution was spelled?”

He adds: “White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them. The only ones who suffer when they are made to feel inferior is us.”

In his journey to free his family from slavery, Jim commits a string of crimes towards a shocking denouement that, perhaps unnecessarily, rewrites his entire relationship with Huck.

Everett introduces a significant change: While Twain’s novel was set in the 1840s, James is set on the cusp of the civil war, with a burgeoning abolitionist movement against slavery.

But the result is a poignant yet powerful study of racial relations in a bygone era and a captivating homage to Twain’s original work.

If you like this, read: Longbourn by Jo Baker (2014, Black Swan, $23, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3WfPbxJ). In a retelling of the events that unfold in Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice (1813), British author Baker provides the story from the servants’ perspective at Longbourn, the Bennet family home.