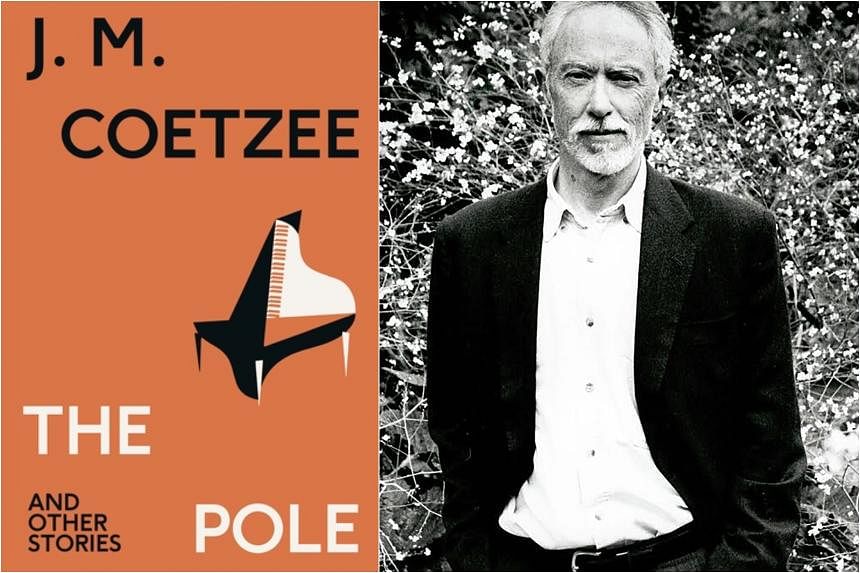

The Pole And Other Stories

By J.M. Coetzee

Short stories/Penguin Random House UK/Paperback/255 pages/$22.66/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3I2u75f)

Four stars

At the grand old age of 84, winner of not just two Booker Prizes, but also the Nobel Prize for Literature no less, South Africa-born writer J.M. Coetzee has nothing left to prove. His body of work speaks for itself.

Thus, in comparison to his earlier, sternly austere novels, this collection of short stories feels somewhat lightweight on first encounter, especially for long-time fans used to the unsparing glare of his denser works. Could it be that Coetzee has mellowed in retirement?

These mostly brief tales, which have appeared in assorted publications in various languages over the past two decades, flirt with familiar Coetzee themes and feature recurring characters.

Elizabeth Costello, the protagonist of the titular 2003 novel, reappears in four stories sandwiched between two other tales.

The Pole is the opening salvo, the longest story taking up 146 pages. First published in Spanish translation in 2022, this beguiling tale centres on a 40something Spanish woman, Beatriz, who develops a relationship with 70-year-old Polish pianist Witold.

There is a characteristic Coetzee slippery post-modern slyness to the prose. Paragraphs are numbered and the first line inserts the author in the narrative: “The woman is the first to give him trouble, followed soon afterwards by the man.”

As the author goes on to introduce his characters, the line between fiction and reality is blurred as he elides into the more conventional third-person narrative and then switches to first-person narrative. That the story is not jarring despite these abrupt changes in perspective is testament to Coetzee’s mastery of language and narrative.

The Pole also establishes the main motif that unites these stories – death and all its infinite terrors and implications.

In this digital age where any topic seems to be grist for the social media mill, one of the rarest taboos seems to be discussing plainly the indignities of old age, the fear of death and the bureaucratic complications of the latter. And this is where Coetzee focuses his gaze, understandably given his personal proximity to such matters.

Beatriz, seemingly content with her life as a busy tai tai whose husband occasionally strays and whose grown sons are distantly successful, is a practical woman.

At least that is what she tells herself and presents to the world. Yet, she is susceptible to female vanity, flattered despite herself by Witold’s awkwardly blunt declaration of love and gawky literary allusions to Dante.

This uncomfortable affair is classic Coetzee territory – he never romanticises and strips characters’ emotions and frailties bare with his razor-sharp authorial scalpel.

Nonetheless, The Pole feels gentler than previous work. There is even the hint of a sorrowing empathy for the tall, awkward Witold who, after death, leaves a pile of adolescent love poems for Beatriz.

The Costello stories revisit classic Coetzee themes. For instance, As A Woman Grows Older recalls the postmodern equivocations of Elizabeth Costello, the novel.

The Old Woman And The Cats subverts the cliche evoked by the title with a Socratic debate between Costello and her son John that references Coetzee’s The Lives Of Animals (1999).

The Glass Abattoir, a striking image and concept, similarly revisits the topic of animal rights, interrupted by a suspiciously personal lament about ageing from Elizabeth: “I used to be able to take things to the next step, but I no longer seem to have it in me, that ability. The cogs are seizing up, the lights are going out.”

Yet, Coetzee refuses to take that last step towards the personal, maintaining a strict narrative distance from Elizabeth by taking the perspective of the son in three stories.

In The Old Woman And The Cats, The Glass Abattoir and Hope, John is annoyed by his mother’s idiosyncrasies and intractability. In John’s affectionate exasperation, Coetzee keeps the reader balanced on the thin edge – between empathy for John and sympathy for Elizabeth.

The last tale, The Dog, is barely a story but a six-page sketch about a battle of wills between a female cyclist and a neighbour’s guard dog she passes every day.

Summarised thus, the stories sound slight. Yet, taken in the context of Coetzee’s thematic obsessions, there are darker undercurrents here that long-time readers will pick up on.

Whether it is confronting the messy realities of death that leaves a trail of material and emotional debris for the living to clean up, or unpicking the intricacies of the familial and human ties, this collection turns out to be a potent distillation of lessons learnt over a lengthy life.

If you like this, read: Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee (Penguin Books, Paperback, 224 pages, $23.07, Amazon.sg amzn.to/3uFVq2k). In this compact 1999 novel that won Coetzee his second Booker Prize, an English professor flees a sex scandal by retreating to his daughter’s farm, but a violent incident forces the duo to confront uncomfortable truths in post-apartheid South Africa.