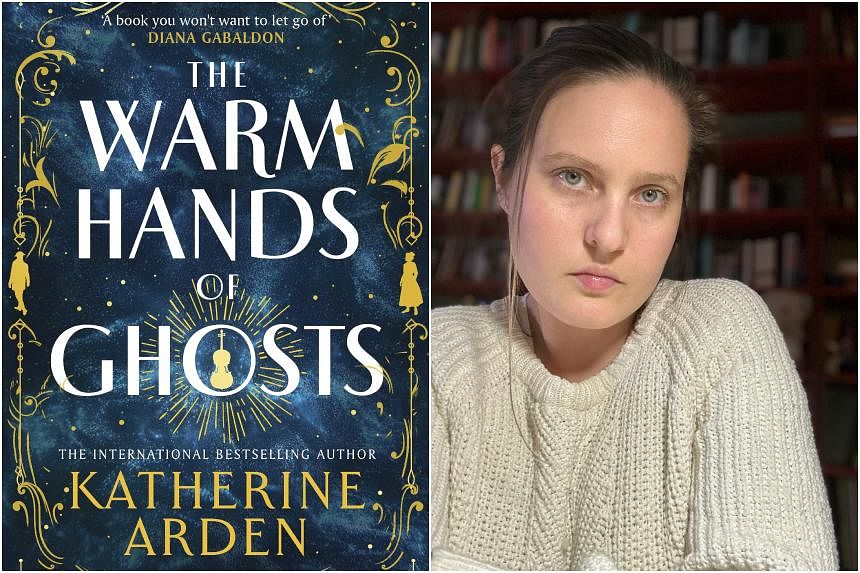

The Warm Hands Of Ghosts

By Katherine Arden

Fiction/Penguin Random House UK/Paperback/381 pages/$31.45/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3wNRMUO)

4 stars

Fans of Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy (2017 to 2019) can be forgiven for being puzzled on their first encounter with her latest book.

Unlike the dreamy fairy-tale world immediately conjured in her previous books, The Warm Hands Of Ghosts opens in startlingly realist mode.

There is an author’s note about the battle of Passchendaele in Belgium during World War I in 1917, a detailed map of the cities of Poperinghe and Ypres vis-a-vis the Western front, and a box arrives in the town of Halifax in Nova Scotia, Canada.

It contains a uniform and dog tags belonging to Freddie, Laura Iven’s younger brother, a soldier fighting on the aforementioned Western front. It is a bleak opening, made even bleaker by the circumstances Arden puts her heroine in.

Laura is herself a shell-shocked survivor of the front, sent home after being injured in a bombardment of the casualty clearing station in Brandhoek where she was a combat nurse.

She returns to her home town of Halifax, seemingly distant from the war and therefore a haven, just in time to experience another disaster, drawn from real life. The French cargo ship Mont Blanc, carrying high explosives, collides with another vessel in Halifax’s harbour.

The resulting detonation is one of the biggest non-nuclear explosions on record and Laura’s parents die in the catastrophe. Her father is among the firefighters on the water while her mother, watching the fire from their home, is shredded by flying glass from the window.

These horrors are piled one upon the other in just the opening page.

In the hands of a less subtle writer, this narrative might have degenerated into bombastic melodrama. Yet Arden delivers, in understated fashion, a deft sketch that sets up the premise, and promise, of this tale.

Just when the reader thinks the story is mired in too much depression, the B plot kicks in – Freddie wakes up buried in mud with a fellow soldier. The twist, of course, is that the soldier, Winter, is German, the enemy. Yet, as the duo struggle to escape their death trap, they come to rely on the other for solace, for survival and for something more.

As the story turns into a mystery-cum-quest – how did Freddie’s jacket end up in Halifax, how will Laura find Freddie – Arden spins out these two narrative strands masterfully, weaving in themes not just of love and loyalty, but also the ethics of war and care, as well as a very postmodern querying of the role of stories in trying times.

She does all this not just with tender thoughtfulness, but also in lyrical prose that keeps the reader turning the pages in spite of the grimness of the setting.

Arden has a knack for describing horrors in a way that packs a punch without being lurid.

Laura’s father remembers the bodies from the Titanic disaster floating in the waters “like dynamited fish”.

Freddie kills in order to save Winter and Arden writes of his promise to keep Winter alive: “It was a vow he’d written in another man’s blood, and now it was all he had left in the world.”

There are the little flashes of insight that detonate along the way, lighting up the narrative like signposts.

Laura, recalling her mother’s obsession with the end of the world, thinks: “Armageddon was a fire in the harbor, a box delivered on a cold day. It wasn’t one great tragedy, but ten million tiny ones, and everyone faced theirs alone.”

Laura’s father, in his cups, dismisses technological progress with a bitterness that nonetheless resonates in this 21st-century world of climate catastrophe and renewed nuclear fears: “Give people God’s power… It just writes their stupidity larger and larger until they drown the whole world. Our hands get bigger and our spirits shrink.”

Fans of Arden’s previous books, which draw heavily on fairy-tale and folk-story tropes, will do well to read this book as closely for the literary breadcrumbs scattered throughout. The allusions are more subtle than the obvious enchanted fairy-tale world of Winternight.

The names of Laura and her brother Wilfred Charles, who “wrote wretched poems”, are obviously nods to WWI poet Wilfred Owen. The elderly Parkey sisters – Agatha, Lucretia and Clotilde – who shelter Laura and conduct seances are an echo of the Moirai, the ancient Greek sister trio of fate and destiny.

And then there is the mysterious, violin-playing Faland, who bargains with desperate souls to trade stories about their deepest fears for material and emotional relief from the unforgiving reality of the war zone. Readers of Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story will know how that Faustian bargain turns out.

Whether Faland is the devil or not is left open to interpretation. But identifying Faland’s true nature is not really the point of this book.

Arden, in the fashion of countless bards and storytellers before her, is employing time-worn tactics of myth to illuminate the human condition.

This wide-ranging, sorrowful and cautiously hopeful tale is a thoughtful, heartrending exploration of humanity and hope amid death and devastation. And one cannot ask for anything more, or less, in these trying times.

If you like this, read: All Quiet On The Western Front by German war veteran Erich Maria Remarque (Vintage, 1987, $15.52 for the reissue, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/48SoUrZ). The 1929 classic is about a group of soldiers’ wartime experiences and how trauma shapes their return to civilian life.