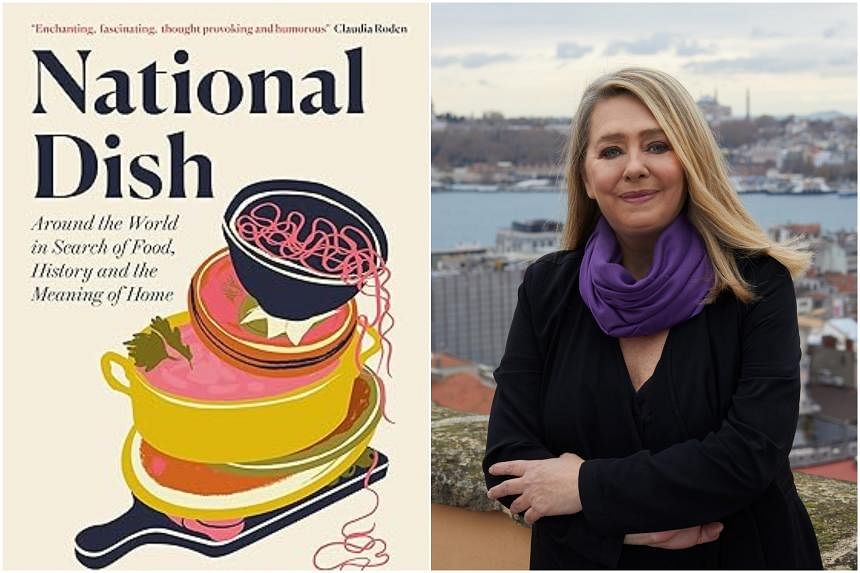

National Dish: Around The World In Search Of Food, History And The Meaning Of Home

By Anya von Bremzen

Food history/One/340 pages/Paperback/$32.91 from Amazon SG (amzn.to/3NPJphb)

Three stars

This book is a good resource for food- and travel-mad Singaporeans, who can Google search and map pin a whole host of eateries across the three continents and six countries covered.

Cookbook author and food writer Anya von Bremzen is well-equipped as a travel host, feeding well-researched nuggets of anthropological, geographic, social and political history in bite-size chapters. She certainly has an ear for the quick sound bite and newsy hook that draws in not just the hardcore foodie, but also the curious passer-by.

The concept for National Dish is simple. Von Bremzen eats her way through signature dishes in each of the six countries she visits – France, Italy, Spain, Japan, Mexico and Turkey – dissecting the process by which a dish defines national identity.

She starts with the pinnacle of Western epicurean refinement – France. The dish is pot-au-feu, literally translated as pot on the fire, a slow-cooked stew with beef, chicken and assorted root vegetables.

Subsequent chapters hopscotch through Europe with token nods to Asia and the Americas.

In Naples, it is the famed pizza Napoletana that claims centre stage, with pasta coming in a photo-finish second. Ramen and rice are the competing carbs in Tokyo.

Spain’s famed moveable tapas feast is a bit of a cheat because this is a multi-plate line-up rather than one dish. Similarly for Istanbul, where the writer opts for the Ottoman potluck rather than a single dish.

As for Mexico, maize is more an ingredient than a dish even if it is the main component of tortillas. Moles, however, are a justifiably famed culinary tradition.

Even in this short summary, the pitfalls of the premise are evident. Trying to name a national dish is a fraught affair. Just look at Singaporeans arguing over chicken rice versus bak chor mee.

One dish cannot hope to encapsulate the diversity of a cuisine.

Yet, food can offer immensely illuminating insights into the geography and history of peoples. At her best, von Bremzen manages to dive deep into the origins of foodstuffs and tease out the multicultural roots of a seemingly monocultural dish.

Ramen, for example, is seen as quintessentially Japanese and one of the country’s most ubiquitous food exports, especially when one counts the omnipresent cup noodle. The not-so-deep roots of the noodle favourite lie in Nankin soba, a noodle in a salty, fatty pork-based broth that first appeared in Yokohama’s Chinatown in the late 1880s.

Its popularity with the Japanese took off during the reconstruction period post-World War II. The United States dumped surplus wheat supplies in Japan, resulting in plentiful and cheap noodles.

While the various chapters often contain eye-popping, engaging bits of trivia about foodstuffs, the reader also has to wade through von Bremzen’s occasionally purple prose – she describes a limoncello as “savagely chilled”.

What this reviewer has more qualms about is the way the writer, a contributor to such august American print food magazines as Food & Wine and Saveur, betrays her deeply Western approach to food in a couple of statements.

She celebrates how French cuisine was the “first” food culture to be inscribed in Unesco’s list of intangible cultural heritage, but a couple of paragraphs later, dismisses in a line the fact that Mexican cuisine was also inscribed in the same year.

She is blithely unquestioning about the position of privilege from which she writes. In each city, she has insider guides who open doors for her and introduce her to key food personalities.

Given such access, it seems a missed opportunity when her narrative strays from the cuisine to personal anecdotes. The Oaxaca chapter digresses rather self-indulgently into her impromptu nuptials with her long-time companion rather than focusing on the deep history of moles.

Her tone is also uneven. The introductory chapter on Paris displays a deep ambivalence towards French cuisine. The Russian-American author, born in the Soviet Union, describes her teenaged first impression of Paris with surprising vitriol as “nothing but despotic prix fixe menus, withering classism and Haussman’s relentless beige facades”.

Von Bremzen seems unable to decide whether she wants to write extended travelogues, in-depth food essays or a personal foodie memoir, so the essays have elements of everything to the detriment of the overall tone and depth.

The best way to approach this collection, therefore, is to treat it like an eccentric, oversharing acquaintance rambling on about her life experiences at dinner. It is more a buffet of tasty nibbles rather than a truly satisfying feast.

If you like this, read: The Untold History Of Ramen: How Political Crisis In Japan Spawned A Global Food Craze by George Solt (University of California Press, 240 pages, $48.26, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/48K3mOB), a surprisingly accessible academic deep dive that tracks the evolution of ramen from a cheap fix for the Chinese community to easy post-war nutrition to a new millennium embodiment of culinary geekery.