As if the world doesn't have enough on its hands with a pandemic that's proving difficult to control, we now have a fresh worry: tensions boiling in the subcontinent between Chinese and Indian troops in the far north and north-east of the area, and between Indians and Pakistanis in Kashmir.

Last weekend, a serious skirmish took place between Chinese and Indian troops in the north Sikkim sector in which a young Indian lieutenant apparently struck a Chinese major in the face after the latter appeared to menace an Indian captain, shouting "This is not your land... just go back!"

Although the headstrong young lieutenant, a third-generation soldier, was immediately transferred out by higher authority, sections of the Indian media, including a publication close to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, have hailed him as a hero.

Separately, clashes between Indian and Chinese soldiers erupted at a spot called "Finger 5" on the northern bank of the Pangong Tso Lake in eastern Ladakh, an area bordering Xinjiang and Tibet that saw pitched battles in the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict.

Two-thirds of the water body is controlled by China and the Finger 5 incident apparently involved 250 troops using rocks and iron rods, leaving injuries on both sides.

Over in Kashmir in the past fortnight, India lost an officer of colonel rank, a major and three soldiers. They died storming a hideout in troubled Kupwara district to rescue hostages taken by intruders, described by India as Pakistanis belonging to the Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorist group. Fearing a repeat of the Indian retaliation seen in February last year following a suicide bombing in Kashmir, the Pakistan Air Force has flown fighters close to the Line of Control, including night sorties.

The summer months when the Himalayan glaciers melt with the arrival of warmer weather are generally the silly season for the low-intensity skirmishes that routinely take place along the frontiers.

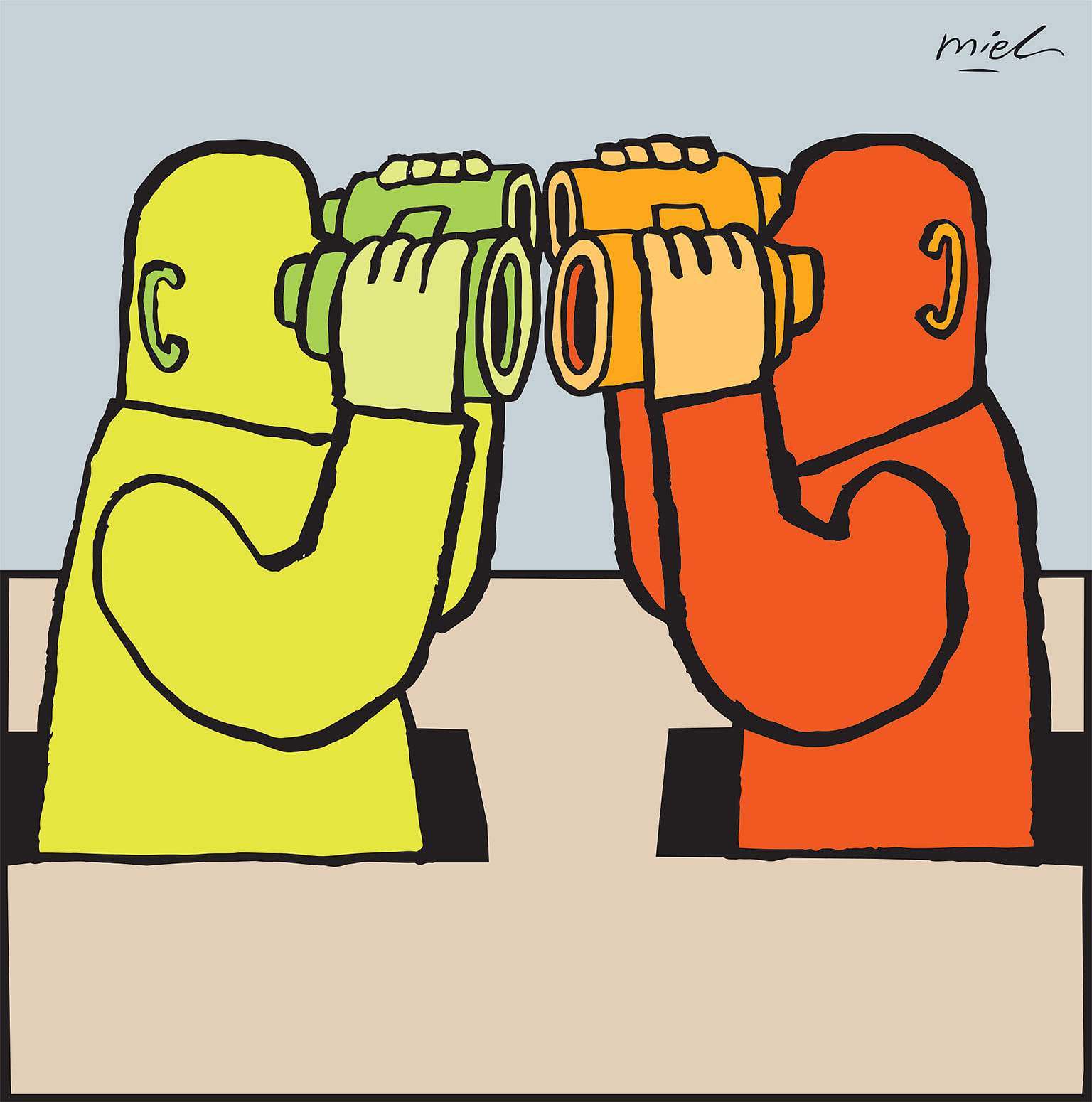

While mortar and machine gun fire is frequently exchanged on the India-Pakistan line, the Chinese and Indians are careful to only confront each other with guns pointed to the ground. Such encounters take place when border patrols run into each other along their undemarcated line and one side thinks the other has pushed too far.

Instead, there is jostling and warnings - and in the rare instance as happened over the weekend - a flying fist.

Three years ago, Indian troops entered Bhutanese territory to push out Chinese troops from a key tri-junction in the Doklam area, whose control would have given China enormous advantage in checking India's access to its seven north-eastern states in a conflict situation. The area is considered so vital strategically that China reportedly had offered Bhutan 540 sq km of territory in exchange for the 89 sq km of territory it sought from the kingdom.

NEW STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT

This time, however, frictions are rising amid a marked change in the strategic environment. That lends additional danger to the scenario and the risks of a significant escalation on the various fronts.

India's steadily advancing strategic embrace of the United States, at a time when US-China ties are worsening by the day, has caused worry in Beijing. The weapons India has begun to acquire from the US, and a series of bilateral agreements, have increased inter-operability of the forces. Beijing also suspects a noose is sought to be drawn around it by the Quadrilateral Dialogue or Quad, which pulls in the US, Japan, Australia and India.

After initial hesitation about upsetting China, Quad nations held their first foreign minister-level meeting in New York last September. Earlier this month, the four decided to consult weekly at officials level. Although the subject for now is health, there are suspicions about where the consultations could lead to, given the developments around East Asia.

A Quad-Plus meeting was held in the second half of March that included New Zealand, South Korea and Vietnam. Since that meeting, Chinese coast guard actions against Vietnamese fishing vessels in disputed waters saw the Philippines voicing rare public criticism of China, as it backed Hanoi's position. A second Quad-Plus meeting this week was raised to the level of foreign ministers, and this time brought in South Korea, Brazil and Israel.

New Delhi also is in danger of appearing to play too closely to Washington's decoupling playbook when it comes to access to its 1.4 billion-size market, reducing Beijing's incentives to be accommodative of Indian concerns.

After pulling out of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership talks last November on fears of being swamped by Chinese goods, India recently announced it would no longer give blanket permission for countries with which it shares "land borders" - widely interpreted as a euphemism for China - to invest in its market.

While this does not amount to a ban, only increased scrutiny, it comes at a particularly sensitive time for China, which fears US pressure is shutting it out of key foreign markets. New Delhi's decision followed a small, opportunistic Chinese investment in India's biggest mortgage lender as stock prices collapsed in the wake of the pandemic.

India has its own list of grievances about Chinese insensitivities, starting with Beijing's steadfast support for Pakistan. Beijing announced the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which runs partly through territory that is the subject of a Pakistan-India bilateral dispute, without consulting New Delhi. That one act caused capital-short India to turn its back on the Belt and Road Initiative.

Subsequently, China's repeated "technical holds" on naming Pakistan-based Masood Azhar, head of the Jaish-e-Mohammed militant group, to a list of global terrorists identified by the United Nations irked India severely.

Azhar, whose group claimed responsibility for the February 2019 Kashmir suicide bombing that nearly brought India and Pakistan to war, was finally named to the group in May last year after intense pressure applied by Washington and Paris.

THE KASHMIRI CANKER

Meanwhile, Kashmir remains the perennial canker between India and Pakistan.

The deaths of the Indian soldiers there in the past fortnight follow on the heels of the loss last month of five commandos killed along the Control Line in Kashmir's Keran sector during a close-quarter firefight with insurgents attempting to infiltrate the line.

The incident prompted a visit to the area by Indian army chief Manoj Naravane, who accused Pakistan of "exporting terror" at a time when the world was preoccupied with the coronavirus.

Senior commanders generally step in to calm situations such as these. However, India has proclaimed a "new normal" since February last year when it went for significant escalation, using fighter aircraft to hit a purported terrorist camp inside Pakistani territory.

This took place amid the heat of the election campaign after an Indian Kashmiri suicide bomber sent by Jaish detonated himself on Feb 14, taking with him the lives of 40 Indian paramilitary troops. Following the air strike, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had spoken of a "new convention and policy" towards Pakistan, taken to mean he would not be deterred by its nuclear weapons. On the stump, he has said his own nukes were not "crackers meant to be burst during Deepavali".

For its part, Islamabad has shown it does not lack resolve; in a dogfight that followed its own warning strike close to an Indian military facility, an Indian pilot was shot down and later returned.

The danger is that all of this comes when all countries involved are at a weak moment; the pandemic has ravaged what anyway were wheezing economies whose swagger had been significantly curtailed. In India, for instance, pensions aside, this year's defence budget is just 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product - there simply is no money for more, given the multiple other challenges the country faces.

Rather than help reduce tensions, weakness can sometimes cause situations to escalate. A spark here and there could lead to wider conflagrations if, for instance, a nation unwilling to commit ground troops is tempted to reach for stand-off weapons, such as missiles.

MODI'S DISENCHANTMENT

So far, all concerned seem to be inclined to tamp down the situation. India's General Naravane told journalists on Wednesday that the incidents on the China border had "no connection with any domestic or international situation prevailing today" and the current ones, too, would be handled "as per protocol between the two countries". A Chinese spokesman has echoed similar views, saying his nation was committed to maintaining peace and tranquillity.

While India-Pakistan ties were always fraught given their tortured history, the pity about the Sino-Indian relationship is that no Indian leader had stepped into the prime minister's office with such a positive attitude towards China as Mr Modi.

Today, admiration and the instinct to emulate China, which led him to promote Gujarat as "Guangdong of the East", have soured into deep scepticism. This is driving him to take his nation, long admired for its independent foreign policy, towards what looks like a "non-treaty ally" relationship with Washington. In turn, this feeds into apprehensions about New Delhi turning into a lackey of the US.

Ironically, Mr Modi had been banned from entering the US for more than a decade following his mishandling of communal violence early in his tenure as Gujarat state minister.

The weather forecast for the Indian subcontinent is for a normal monsoon. Hopefully, that will cool what could be a hot summer on the borders.