SINGAPORE - Allegations of corruption had cropped up in relation to the rental of two bungalows near Queensway by Mr K. Shanmugam and Dr Vivian Balakrishnan.

On Wednesday, two reports – one by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) and the other by Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean – were submitted to Parliament. Here are seven key questions the findings sought to address.

1. Was there any corruption on the part of the ministers and officials involved?

CPIB, directed by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong to investigate the matter on May 17, found no evidence of corruption or criminal wrongdoing in the two rental transactions.

Tenancy rules were applied fairly with no corrupt intent in the processing of the rentals, and no preferential treatment was given or privileged information disclosed to the ministers and their spouses, the anti-corruption watchdog found.

For instance, both ministers had not been offered the properties under the table.

Mr Shanmugam had asked the Ministry of Law’s then deputy secretary for a list of properties available to the public for rent and had visited them. All of them had a “for lease” sign prominently displayed.

Dr Balakrishnan, meanwhile, had found out about 31 Ridout Road through his wife, who had gone past the property and come across the “for lease” sign.

CPIB, which reports directly to PM Lee, spent slightly more than a month on the investigation, speaking to the two ministers, their spouses, former and current officers from the Ministry of Law (MinLaw), Singapore Land Authority (SLA) and National Parks Board (NParks), and others.

SM Teo’s review had relied on CPIB’s investigations to establish the facts.

CPIB’s investigation papers were submitted to the Attorney-General’s Chambers, which has reviewed the papers and directed that “no further action be taken as the facts do not disclose any offence”.

2. Did any conflict of interest arise?

A Code of Conduct for Ministers has been in place since 1954, and was last updated in 2005. It expects ministers to be scrupulously above board, and ensure that there is no real or perceived conflict between their official duties and private interests.

In the case of 26 Ridout Road, a conflict of interest could have arisen as Mr Shanmugam’s Law Ministry oversees SLA, which manages the property.

But SM Teo found that both ministers, and the public officers involved, had duly declared any potential conflict and followed proper processes to prevent any from arising.

Mr Shanmugam, for instance, had recognised the potential conflict of interest and had taken steps to prevent any actual conflict from arising by removing himself from the chain of command and the decision-making process in relation to the rental.

He had informed the ministry’s then deputy secretary about his plan to rent the property, and also told the deputy secretary to approach then Senior Minister of State for Law Indranee Rajah in case any matter had to be referred to the law minister.

At the same time, Mr Shanmugam informed SM Teo that Ms Indranee would approach SM Teo should the matter have to go beyond her.

In the end, SLA did not raise any matter to MinLaw during the entire process, the report found.

In the case of 31 Ridout Road, no conflict arose because Dr Balakrishnan’s official responsibilities did not include overseeing the SLA.

The managing agency responsible for 31 Ridout Road was also explicitly told by SLA that “there was no policy for VVIPs (very very important persons)“ and all tenants were to be treated equally.

3. Did the ministers benefit from privileged information?

The CPIB found that they did not.

Questions had been asked about the level of transparency in the marketing of the properties, such as whether members of the public also knew they were available for rent, and on the bidding process.

The Ridout Road estate was under the management of professional third-party managing agents – including DTZ Facilities and Engineering and Colliers International Consultancy and Valuation – which determined how to market the properties based on prevailing market conditions, the report said.

Both properties were advertised with “for lease” signs at the time, and 31 Ridout Road was also listed on the State Property Information Online website used to put out tenders for such state properties.

Given the low demand for the two properties, they were leased out through the direct tenancy process instead of an open bidding process. This is when prospective tenants are considered by SLA as long as they meet the stipulated financial criteria and their bid is not below the guide rent.

4. Did the ministers benefit unfairly from favourable rental rates?

Both ministers paid rents at fair market value, and not below market valuation, the report found.

Dr Balakrishnan initially paid $19,000 a month, more than the guide rent for 31 Ridout Road.

This was revised to $20,000 a month upon renewal for three years in October 2022.

Despite the guide rent for 26 Ridout Road being imprecisely stated by SLA, Mr Shanmugam paid rent of $26,500 a month, equal to what the guide rent should have been.

The review also confirmed that rentals paid were in line with those of other properties in the area.

In 2018, the rental per floor unit area for No. 26 was $30.94 per sq m per month.

This was comparable to those of other Ridout estate properties, ranging from $26 to $33.33 per sq m per month.

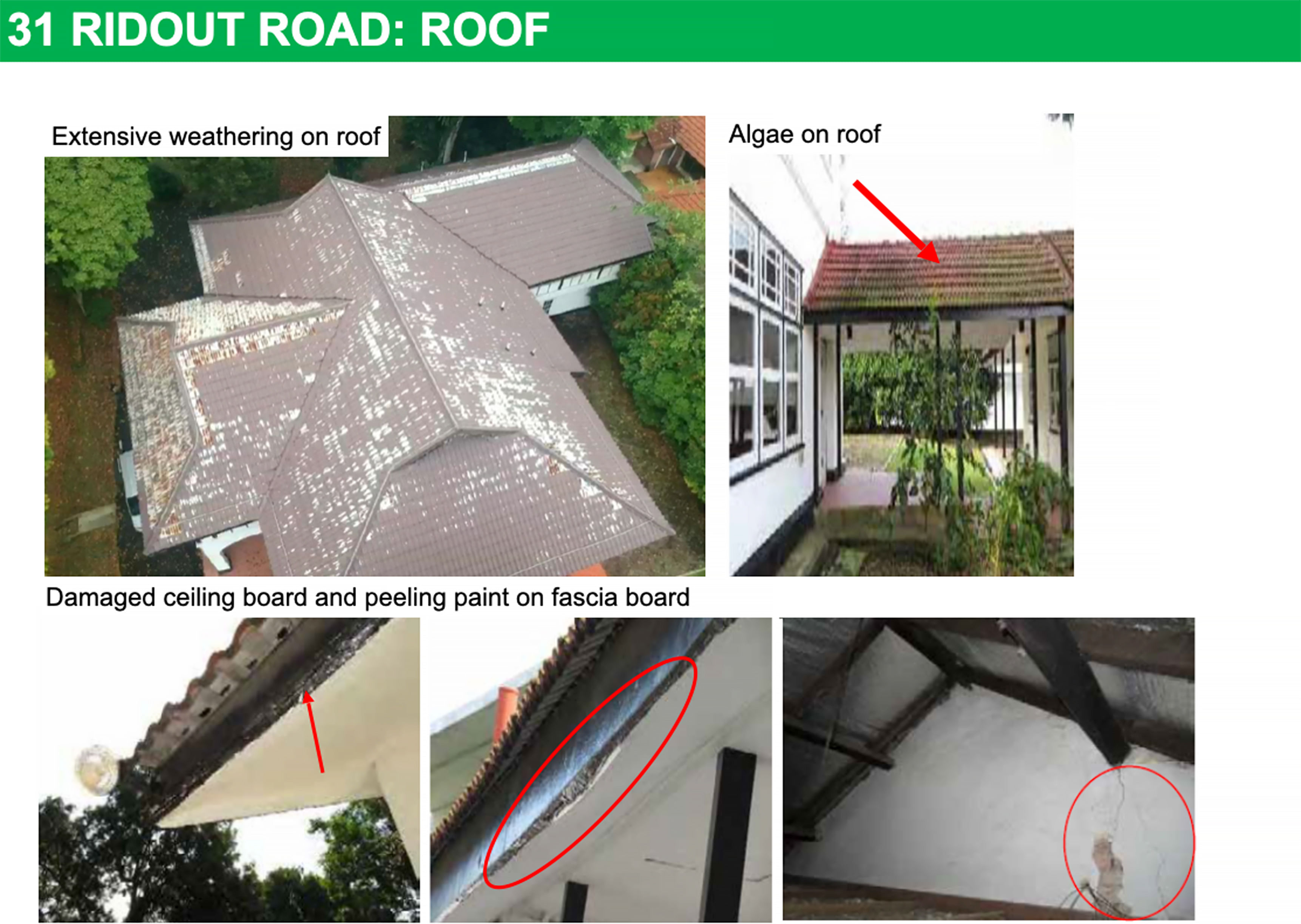

The rate for No. 31 was $23.05 per sq m per month, slightly below the $25 to $33.33 per sq m per month for other Ridout estate properties in 2019.

But this was due to the condition of the property, said the report, and $23.05 was still comparable to other properties of average condition at the time.

When the tenancies of both properties were renewed after the initial three years, a revaluation was done to peg the rentals to the market rate.

Hence, No. 26 was renewed in June 2021 for three years at $26,500 a month, while No. 31 was renewed in October 2022 for three years with a rent increase to $20,000 a month.

Said the report: “In summary, the rental of the two properties did not deviate from the prevailing SLA guidelines and approaches in renting out black-and-white bungalows for residential purposes.”

5. Did the ministers get unusually long tenancies?

No. The tenancy terms both ministers received were in line with SLA’s policies for the residential properties the agency manages, said the report.

Mr Shanmugam received a tenancy term of 3+3+3 years for 26 Ridout Road, while Dr Balakrishnan received a tenancy term of 3+2+2 years for 31 Ridout Road, with a subsequent extension of 3+2 years at first renewal.

This is within the maximum allowable tenancy term of 3+3+3 years that SLA can grant at any one time.

While SLA grants tenancies on two- or three-year terms, the agency considers factors such as how much the tenant will likely spend to improve the property, in deciding whether to grant a longer tenancy.

This is because all approved improvements undertaken by tenants will become the property of the Government when the property is returned, and a longer tenure would allow for the amortisation of such expenses over a longer period.

For 26 Ridout Road, SLA had taken into account that Mr Shanmugam’s wife had committed to undertake improvement works costing more than $400,000. For 31 Ridout Road, Dr Balakrishnan’s wife had committed to carrying out works totalling more than $200,000.

6. Were works undertaken beyond the usual practice?

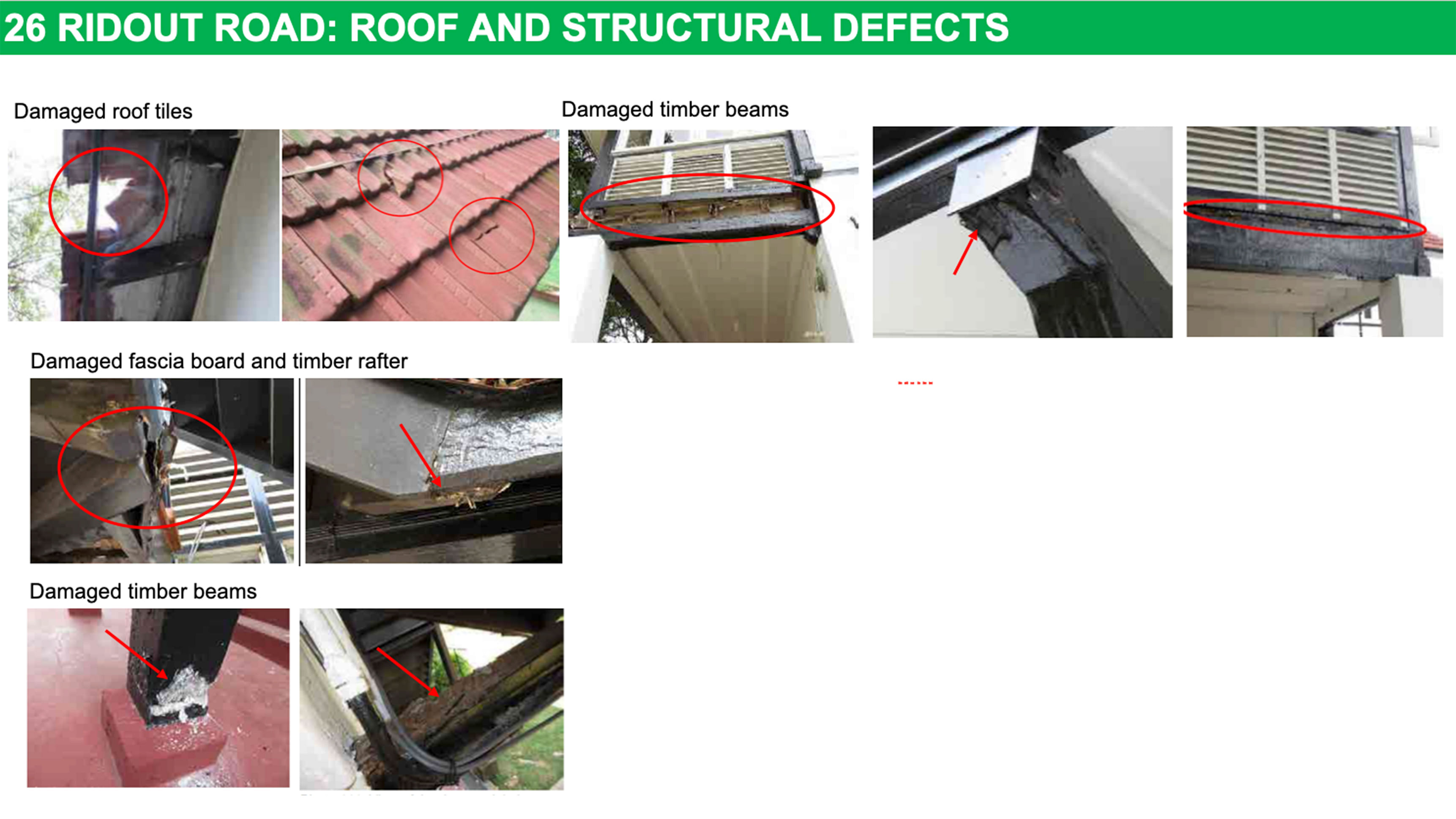

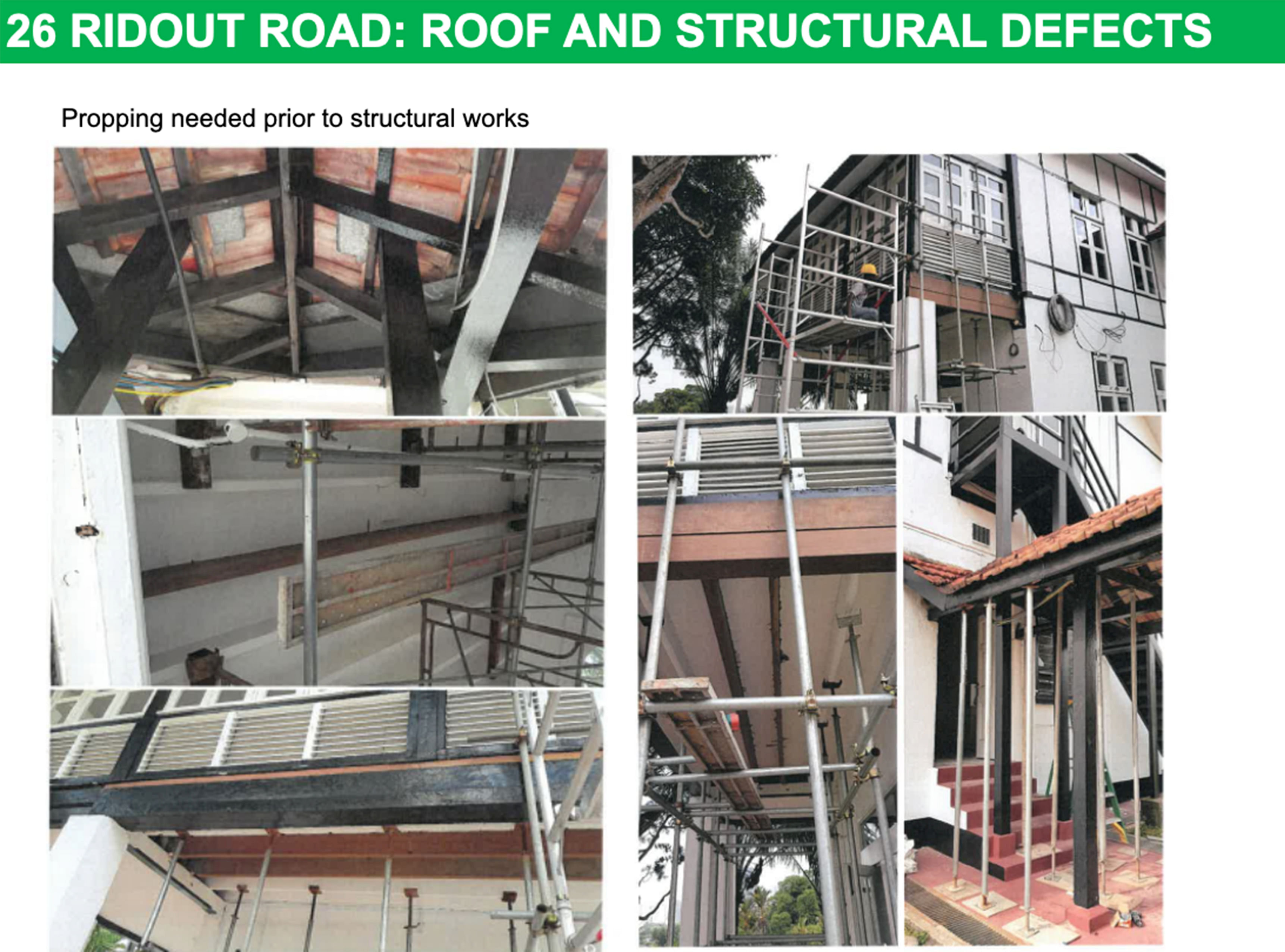

Having examined SLA’s policies and practices for managing residential policies, the report concluded that works it undertook for the two properties in question did not go beyond what the agency normally did as a landlord.

For 26 Ridout Road, SLA had agreed to clear an adjacent land plot due to significant disamenities arising from vegetation there which could affect the safety of tenants.

While SLA agreed to clear the land and spruce up the property for rent, Mr Shanmugam offered to maintain the plot at his own cost and committed to undertake significant improvement works to the state property.

The review also found that the Law Minister also bore the cost of additional improvement works that went beyond what SLA normally carried out to prepare a property for rental.

For 31 Ridout Road, CPIB found that preparatory works that SLA agreed to undertake were not excessive, and comprised works such as roof repair, plumbing and electrical checks to ensure that the property would be in a functional state for rent.

7. Did improvement works get the required approvals?

Both 26 and 31 Ridout Road were gazetted in 1991 for conservation and are subject to conservation guidelines. However, permission is not required for minor works external to the bungalows and which do not affect the conserved bungalows.

The Urban Redevelopment Authority had therefore earlier advised SLA that no approval was required for the installation of a swimming pool at 26 Ridout Road, which was leased by Mr Shanmugam.

Both properties are also part of the Tree Conservation Area, which means that NParks’ approval is required for felling trees with girth greater than 1m.

SLA had obtained the relevant approvals from NParks for the felling of trees and has kept a record of NParks’ approvals, SM Teo said in his report.