SINGAPORE - In January, when Mr Paul Osmond Thomas George’s heart disease caused him to develop increased fluid build-up in his body, his doctor prescribed a five-day course of intravenous diuretics to be given in hospital to clear the excess fluid.

“I told her (his doctor) that there’s no way that I will want to stay in the hospital,” the 46-year-old said. “I had a hospital stay of about six months (in 2022)... It was very depressing.”

Mr George, who retired early a few years ago, had to be admitted for a bacterial infection at a time when visitors were first not allowed and then restricted due to pandemic curbs. His wife and two children could not see him during the first month of his stay.

When he was referred to the virtual ward pilot programme at Sengkang General Hospital for his latest ailment, he said yes.

During the home stay, a doctor examined him via Zoom every morning, and a nurse came by twice a day to administer the treatment and check on him. He was discharged after a six-day stay.

“I had my ice kachang... You have the comfort of your home and can do whatever you want,” he said.

A virtual ward will become an option in public healthcare institutions here from April, and patients will not pay more for Mobile Inpatient Care at Home (MIC@Home) than they do for acute inpatient care in a public hospital, said Health Minister Ong Ye Kung during the debate on his ministry’s budget on March 6. It will be supported by MediShield Life and MediSave subsidies.

Virtual wards will aid in the shift of healthcare to the community, to help reduce the need for so many inpatient beds, he said.

They are part of a broad swathe of measures aimed at meeting growing healthcare demand from a rapidly ageing population, and managing rising healthcare costs.

Public health specialist Jeremy Lim said: “Conceptually, patients will want to be at home or in the community if they can, given how hard it is to get a good rest in the acute hospital setting, the risk of hospital-acquired infections, and the hassle relatives experience in visiting.

“That said, being in the community is not friction-free either, as meals, toileting, et cetera, will need to be taken care of. Funding to ensure patients and their families are not financially worse off for doing the right thing by moving out into the community would be an important issue to address.”

Dr Lim added that he had previously mooted the somewhat radical notion of paying patients and their families to go home, as this, in effect, provides funding for meals, short-term help and others.

“Equally important would be to grow and mature the home and community care ecosystems, so that patients and families can obtain the care and support services,” he said.

This would mean easy access to home monitoring services, healthy food and special-diet meal delivery, support services like bathing, and ensuring that these are affordable and of high quality.

During the budget debate, the Ministry of Health (MOH) said it will evaluate a pilot for enhanced personal home care services by the end of 2024, before considering whether to expand it islandwide.

Key to the budget debate announcements was a review of national health insurance scheme MediShield Life to better protect subsidised patients against major health episodes, as hospital bill sizes grow and new, ground-breaking treatments emerge. Bill sizes have grown by 5 per cent annually in public hospitals, and by 7 per cent annually in private hospitals, over the last few years, Mr Ong said.

However, this means that MediShield Life premiums will inevitably rise, he said.

MOH’s annual budget has tripled within a decade to nearly $19 billion for the 2024 financial year, making it the second largest in the Government, behind the Ministry of Defence. This makes up some 40 per cent of total healthcare expenditure, which leads to the question of what else must be done to manage costs, said healthcare experts.

Public health specialist Wong Chiang Yin said: “When I was a young officer in MOH in the mid-90s, the MOH budget had just exceeded $1 billion and accounted for about 30 per cent of total healthcare expenditure. Healthcare expenditure in those days was about maybe 3 per cent of GDP (gross domestic product) or slightly less.

“So, in slightly less than 30 years, the MOH budget has gone up... and our total healthcare expenditure has gone up from 3 per cent to 5 per cent of GDP.”

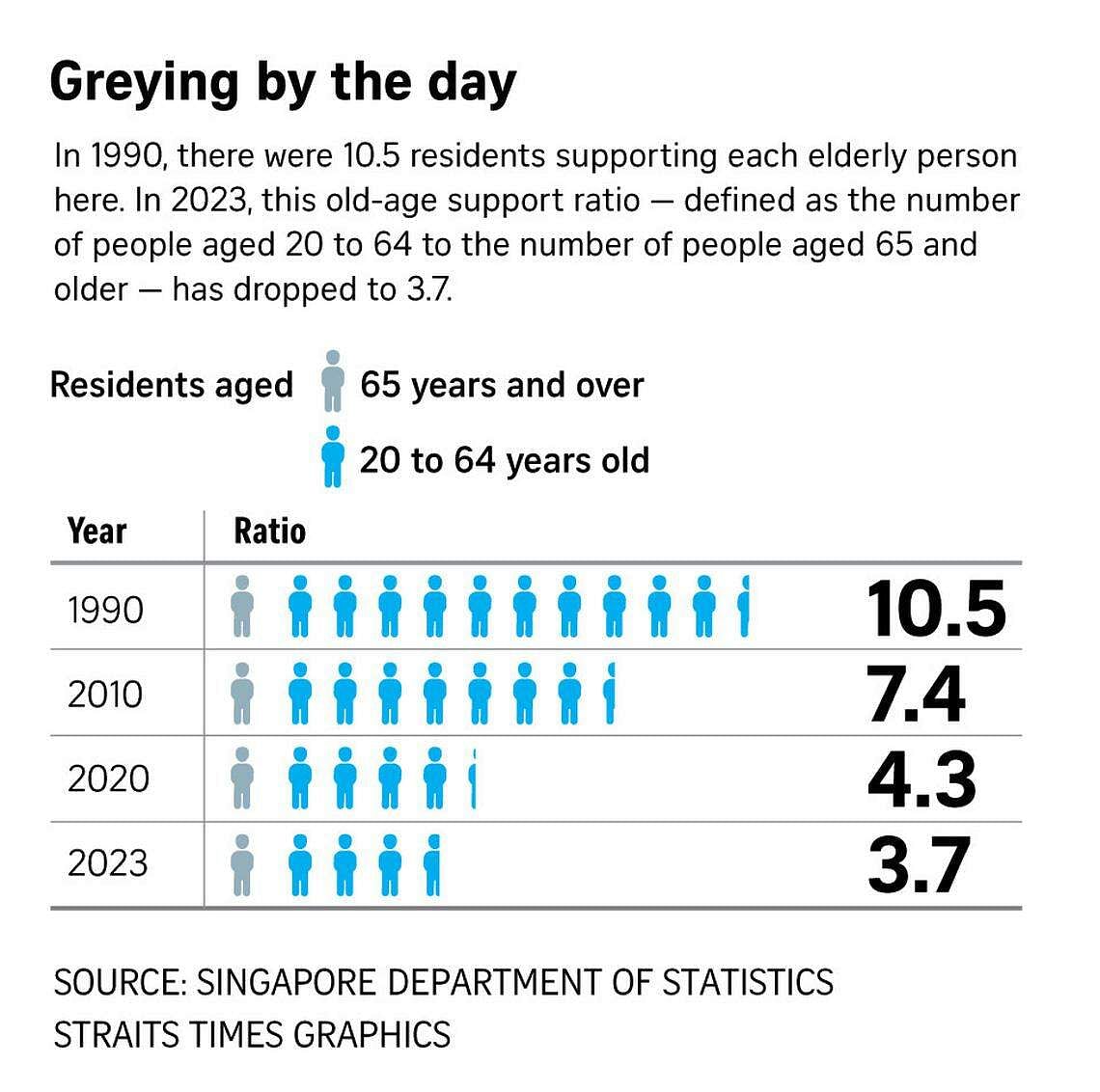

In 2023, there were 3.7 working-age persons supporting each elderly person here. This old-age support ratio – defined as the number of people aged 20 to 64, to the number of people aged 65 and older – was 7.4 in 2010, and 10.5 in 1990, Dr Wong pointed out.

With worsening demographics and a lower sustainable GDP growth rate, the rise in healthcare expenditure and MOH’s budget must slow down going forward if the authorities want to avoid taxing the people more and more, he said.

“So we must then think of getting more bang for the buck, so to speak. This is where Singapore’s healthcare financing is evolving towards.”

Better, cost-effective technology and drugs, as well as home care and virtual wards, will help, he added.

Another way is to reduce the average length of stay (Alos), which has risen from about six to seven days post-Covid-19, as patients have more problems that need attention.

“If we can, through a variety of measures such as Healthier SG, virtual wards, et cetera, bring the Alos down by just one day, then we will need fewer beds,” said Dr Wong.

Health economist Phua Kai Hong said Singapore needs to go into cost-containment mode, particularly given that its fertility rate has dipped below 1 and is well below the replacement rate of 2.1.

He suggested taking a sectoral approach and diving into unsustainable areas, such as some cancer treatments accounting for a major portion of MediShield Life claims.

“Right now, healthcare costs are going up mainly because we are funding new but yet unproven treatments that fall within the patent period. These are mostly cancer drugs and expensive technologies in healthcare,” Dr Phua said.

Singapore has a good mix of healthcare financing – taxation, savings and insurance – and share of public-private contribution, and MediShield Life should cover only new treatments that are cost-effective, though this also hinges on who is deciding this, be it society, doctors or insurers, he said.

He added: “Providers will keep on trying and trying until the cancer patient dies, while patients and families will want to do the same... but do you want to use public money to incentivise research? When do you decide enough is enough?

“A lot of incentives are given to protect the healthcare industry during the patent period. After the patent period, competitors will come in, and the prices will come down to reflect market conditions.”

MediShield Life, being mandatory, is akin to taxation, and subject to public scrutiny, he said.

“On the demand side, we already know that ageing is a problem and costs will rise, but on the supply side, the cost of new healthcare technology and drugs is very high and driving costs up, so society will have to decide when to draw the line and what to pay,” said Dr Phua.

Dr Lim also said the Government and citizens need to come to a common ground on how much of the national Budget should be allocated to healthcare, and what Singaporeans are prepared to forgo as a society if the costs are deemed too high.

This may also require Singaporeans to reset their thinking on longevity, because prolonging life for its sake is not better than having a life spent in good health, Dr Phua said.