SINGAPORE - Early on in negotiations with four armed terrorists who had bombed the Shell oil refinery on Pulau Bukom and hijacked a boat, the Internal Security Department (ISD) made an impossible ask.

The authorities needed volunteer officers in a proposed exchange for the crew members of the Laju, the ferry that the terrorists had taken at gunpoint on Jan 31, 1974, in a bid to escape Bukom after their bombing.

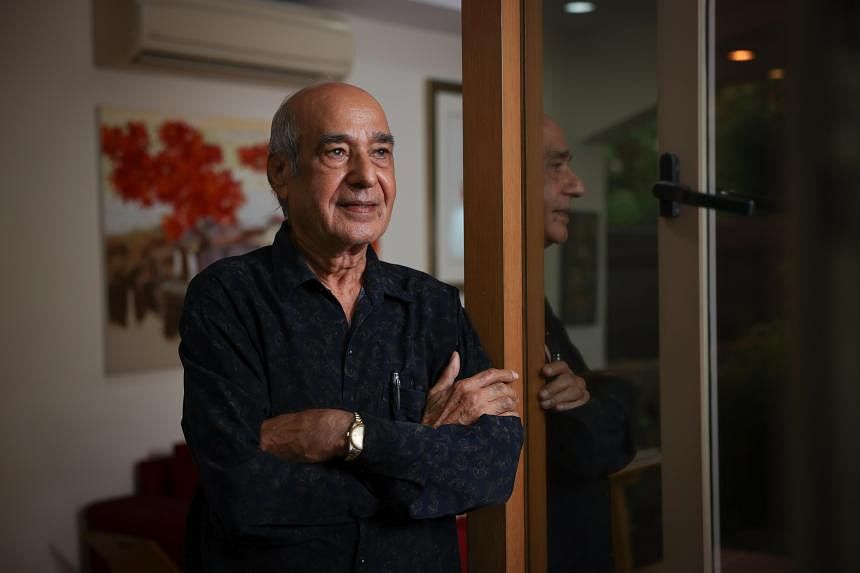

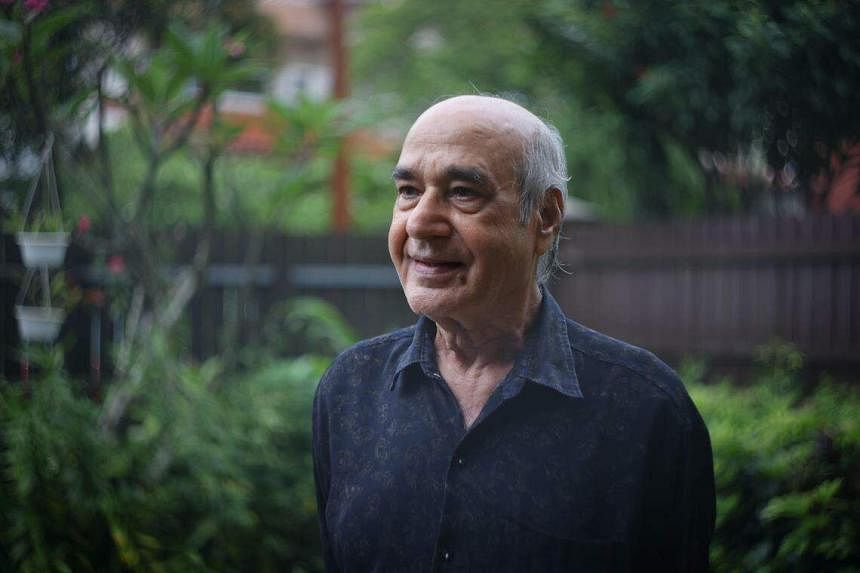

Despite fears for his safety, Mr Saraj Din, then a newly-wed 28-year-old officer with ISD’s counter-terrorism unit, put his hand up to be counted.

“I had to volunteer because I was the officer dealing with the case,” he said in an exclusive interview with The Straits Times to mark the 50th anniversary of the Laju incident.

The story of how the Laju ferry hijacking crisis was defused has been told through the eyes of commanders such as former president S R Nathan, and former commissioner of police Tee Tua Ba, but never from the perspective of a rank-and-file officer such as Mr Saraj.

While the hostage swop never came to fruition, it would not be the last time that the young officer put himself in harm’s way during the case, which was Singapore’s first encounter with international terrorism.

When negotiations were under way, officers found an abandoned car near Labrador Park that had been spotted at Taman Serasi in Tanglin. The car, which the authorities suspected belonged to the hijackers, yielded a set of keys to a flat in Taman Serasi.

A decision was made to storm the flat, but many officers were apprehensive. “They thought the place was booby-trapped, and there may be people inside and there could be a shoot-out,” said Mr Saraj.

He decided to volunteer for the operation, given that he “had a lot of experience with tight situations”, including the race riots that broke out after Singapore and Malaysia separated.

The flat was thankfully unoccupied during the raid, but ISD officers found plastic explosives and some documents, confirming their suspicions.

Meanwhile, negotiations with the terrorists stretched for days, during which two hostages escaped by jumping off the boat. In exchange for the remaining three hostages, the hijackers demanded safe passage on a flight to an Arab country, with a group of guarantors aboard to ensure their safety.

An agreement was reached only after another group of terrorists took the Japanese embassy in Kuwait hostage on Feb 6 and threatened to kill embassy staff unless the Japanese government sent a plane to take the Laju hijackers to Kuwait.

Mr Saraj was informed at about 5pm on Feb 7 to go home, get his passport and get ready to be taken to the airport. Shortly before 2am on Feb 8, a special Japan Airlines flight departed for Kuwait from Paya Lebar Airport with the four hijackers, 13 Singaporean guarantors, two Japanese officials and 12 Japan Airlines crew members.

The 13 were led by Mr Nathan, then director of the Security and Intelligence Division, the Republic’s foreign intelligence service, and included Mr Tee, who had led negotiations as officer-in-charge of the Marine Police (today’s Police Coast Guard), and Mr Saraj.

During the flight, Mr Saraj and the other guarantors sat themselves between the Japanese crew and the hijackers – two men who were from the Japanese Red Army, and two from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Both groups were notorious for collaborating on aircraft hijackings and deadly attacks, including a 1972 massacre at Israel’s main airport that left 26 people dead.

The guarantors had to be alert and vigilant throughout the 10-hour flight, as they suspected that at least some of the aircrew were Japanese commandos.

Mr Saraj said: “We didn’t know if we would come back. Of course, I was worried that at any time something nasty could happen, but I kept myself calm.”

The one decision that still haunts him today was to leave without letting his pregnant wife know about his potential one-way trip. She was used to his long working hours, and had no clue he had left home that evening with his passport.

“She had told me just two weeks earlier that she was expecting our first baby, so it was quite sad to leave and not tell her,” he said, choking up. “I didn’t want to worry her because I was afraid she would get upset and lose the baby.”

When the plane finally touched down at Kuwait International Airport and the winter mist cleared, Mr Saraj was shocked to see the plane surrounded by army tanks and armed soldiers. Instructions from the air tower were that no one was allowed to alight.

Unbeknownst to him, the Kuwaiti authorities had allowed the plane to land on the condition that the terrorists stayed on the plane. The plane was to refuel and depart for another destination.

In his memoirs, Mr Nathan recounted the tough, hours-long negotiations with the Kuwaiti authorities for the guarantors to be allowed off the plane and to return to Singapore, having fulfilled their part of the deal.

At one point, the terrorists who had stormed the Japanese embassy arrived on the tarmac and boarded the plane fully armed with revolvers and grenades. With careful urging by Mr Nathan through Japanese officials, their ammunition was eventually stowed away.

“Mr Nathan managed to hold his ground... The good thing about him was that he was able to size up the situation and act accordingly,” said Mr Saraj.

Some time after, the guarantors were ordered off the plane and into waiting cars. Afraid that the hijackers might insist they be returned to the aircraft as hostages, in Kuwait City Mr Nathan gave each of the officers US$100 from the funds he had brought, and tasked them to disperse by going shopping.

Mr Saraj said the only thing he bought with the money was a US$10 bottle of perfume for his wife.

That evening, the Singaporeans boarded a Kuwaiti Airways plane to Bahrain, before returning to Singapore on Feb 9 on a Singapore Airlines flight.

Mr Saraj finally broke the news to his worried wife when he reached home. Tearing up again, he said: “She didn’t scold me; she said she was proud of me.”

Laju a turning point

Mr Saraj said much changed in the ISD after the Laju incident. Officers were better trained physically and had to keep abreast of geopolitical issues around the region.

“Laju was the turning point in our build-up of resources to handle such a situation, because an incident can happen any time and we must be prepared,” he said, noting that prior to the incident officers largely relied on their instincts and resourcefulness.

In the wake of the Laju hijacking, the police started the Negotiation Team to respond to terrorist and criminal hostage incidents.

Mr Saraj was one of the first officers to join the team and was involved in many security incidents, including the hijacking of Flight SQ117 in 1991, and an incident in 1996 when a drug trafficker and robber held two police officers hostage in a Criminal Investigation Department lock-up.

In 2002, the Negotiation Team was formalised as the Crisis Negotiation Unit (CNU) under the command of the police’s Special Operations Command (SOC). This arrangement was to foster greater responsiveness between the CNU and SOC units, such as the elite Special Tactics and Rescue Unit, said police.

After a storied career of more than 36 years, Mr Saraj left the police force in 1999 as an assistant superintendent of police. He became managing director of a private security firm before retiring in 2011.

Now a grandfather of three, Mr Saraj and his wife celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in August 2023.

Mr Saraj said the 13 officials made a pact not to go public with their accounts of the Laju incident until Mr Nathan did, and the former president did so in his 2011 autobiography.

But just as the ISD still operates in the half-shadows to neutralise threats to Singapore, the steely-eyed veteran said he prefers to keep some parts of the mission untold.

“When I tell my children about my experiences and the cases I did, they say ‘Papa, you should write a book’,” he said. “But no, I think some things are still very sensitive and should be kept secret.”