SINGAPORE - The job applicants are promised at least $500 a month, and the process of filling in the forms with personal information is painless, except for the part asking for confidential banking details.

Employers usually will not ask applicants to divulge the 16-digit number of their automated teller machine (ATM) card, including the confidential personal identification number (PIN), and details like their mother’s maiden name.

But getting such information this way is not part of a scam. However, it is part of a recruitment process for money mules – people who allow criminals to control their bank accounts or help them perform illegal transactions.

With the popularity of messaging platforms like Telegram, which allow people to be anonymous, syndicates have been able to hire foot soldiers with ease, and money mule numbers are on the rise.

In 2019, the number of people arrested or investigated by the police for money mule offences was more than 1,000.

The next year, it went up four times to more than 4,800 people.

In 2021, the numbers shot up, when more than 7,500 people were rounded up. In 2022, more than 7,800 people were nabbed for money mule offences.

Between January and June in 2023, more than 4,700 people were arrested or investigated for being money mules.

A study by the Singapore Police Force in 2023 involving 113 money mules linked to scam cases reported between 2020 and 2022 found that about 45 per cent were 25 years old and younger.

In April 2023, Minister of State for Home Affairs Sun Xueling said it was worrying to see so many people – some as young as 10 – getting arrested for being money mules.

Getting them young

Platforms like Telegram – popular with young people – are quickly becoming favourites with recruiters of money mules, who appear to have stepped up efforts to enlist new helpers.

Over the course of a week in November, The Straits Times observed many advertisements being circulated all day in several Telegram groups and channels known for peddling illegal services, sometimes in a span of just minutes.

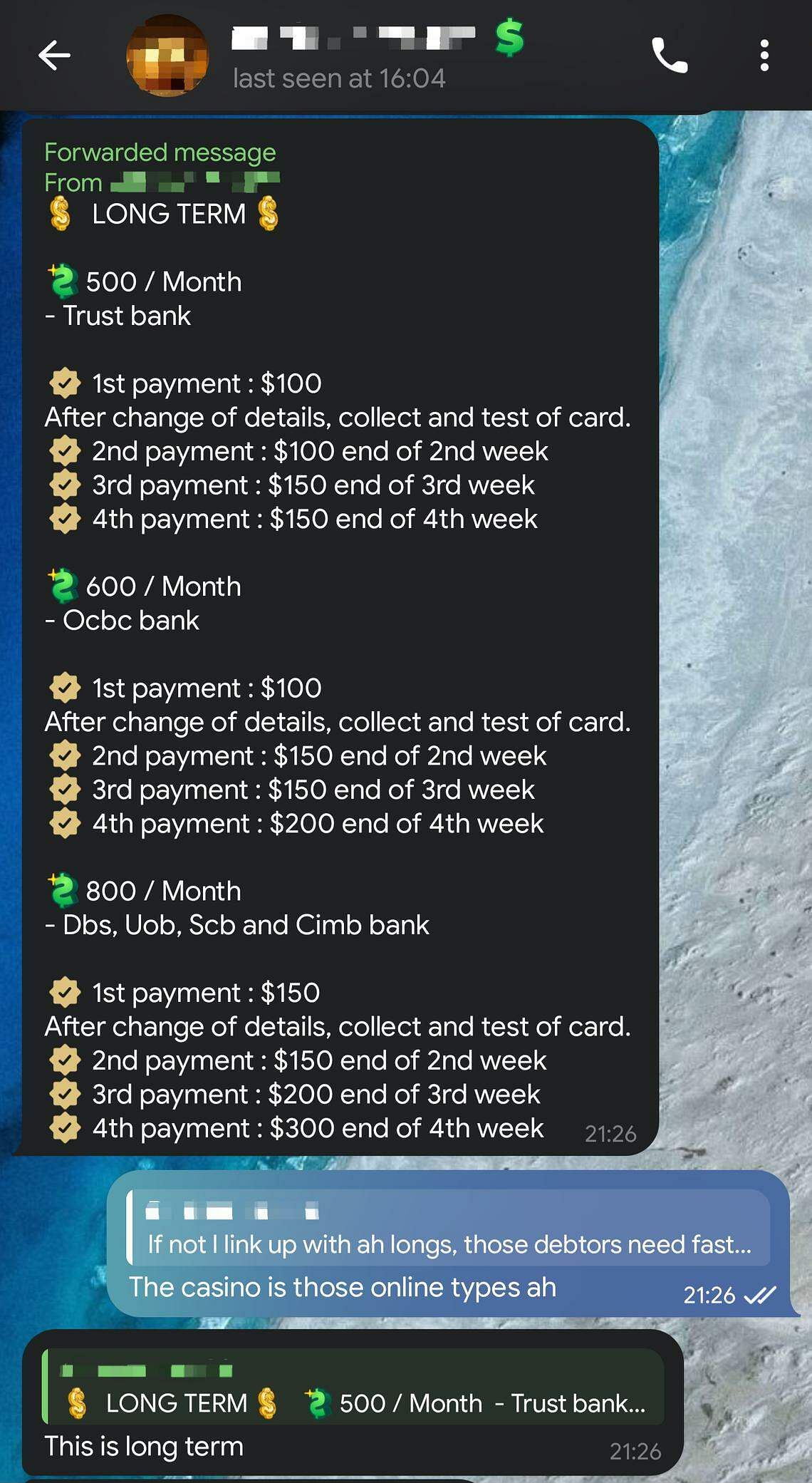

The ads do not waste time with code words – and instead openly ask for bank accounts to “rent”. The amount that money mules stand to earn and the recruiter’s username are also included in the ad.

Posing as an interested party, ST contacted two such recruiters, who both said they were merely functioning as intermediaries, and that the bank accounts were to be used by third parties.

When asked why there was a need to rent bank accounts, one recruiter said these were for sellers of electronic vaporisers – which are illegal in Singapore – and those running illegal gambling activities to move their funds.

He added that some of his clients using the accounts were likely money launderers, but he declined to elaborate.

In some cases, the recruiter said, he would also work with loan sharks to find out which debtors were desperately in need of cash. Once he got their phone numbers, he would offer to bail them out with a cash loan, in exchange for access to their bank accounts.

Rentals could either be for the long term, which meant a month at the least, or on a short-term basis, lasting a week.

Once the time was up, money mules would regain full ownership of their bank accounts. To ensure peace of mind, it was recommended that they change either their PIN or phone numbers with the bank.

Short-term rentals were used for more risky transactions like money laundering, but they earned higher payouts of at least $1,000. However, there was a price – the added risk of having the bank account frozen.

The recruiter recommended long-term rentals instead, which could net at least $500 a month in earnings.

Payment also depended on which banks the account belonged to, among other things.

“Some banks are stricter,” the recruiter said. They have more safeguards in place, and that makes them worth less, added the recruiter, who has almost two years of experience in enlisting money mules.

OCBC Bank is one example of a “stricter” bank, he said. When adding recipients for money transfers, it takes at least 12 hours before the approval comes through and the money can be transferred.

Another consideration is convenience, so banks that have fewer ATMs command a lower price because it takes more trouble to deposit money.

Although coy about the amount of money he was earning from recruiting money mules, the recruiter said he “was taking more” than the sum he paid to mules.

These payments are usually made in instalments, either at the end of the short-term rental, or each week for long-term ones.

The recruiter said he would give the mules guidance if any of the bank accounts rented out were frozen, but other recruiters may not do so.

Another recruiter, for instance, advised this reporter to “come up with an excuse” if a bank account is frozen. He added that feigning ignorance is one means of escape for a money mule when things get sticky.

The authorities closed that loophole in May, when the law was tightened to clamp down on money mules and those who sell their bank accounts or Singpass credentials.

The new rules widened the scope of illegal operations to include rash and negligent money laundering, among other things.

Rash money laundering is when the money mule is aware or has some idea that his actions involve a criminal element. Anyone convicted of the offence faces up to five years in jail, a fine of up to $250,000, or both.

Negligent money laundering is when a person continues with a transaction despite the red flags that any ordinary, reasonable person would have noticed.

Those found guilty of the offence can be jailed for up to three years, fined up to $150,000, or both.

Money mules can also no longer claim they did not know they were selling their bank or Singpass accounts to scammers.

The tougher laws were passed after it was clear that only a few money mules were prosecuted for their actions.

Between 2020 and 2022, the police investigated more than 19,000 money mule cases, but only 236 people were prosecuted, due to the difficulty of proving that they intended to facilitate criminal activities by selling their bank accounts and Singpass credentials.

While they may not be directly involved in making criminal transactions, recruiters are not exempt from the law, said Mr Thong Chee Kun, the co-head of law firm Rajah & Tann’s fraud, asset recovery and investigations practice.

He said: “With more involved roles in the criminal syndicates, they are often punished more harshly than the account holders themselves.”

He added that they could be liable for a range of offences, with money laundering being one of them.

What banks are doing

Banks, on the other hand, generally will not be held responsible, with strict regulations in place to police money laundering.

They also report suspicious transactions to the authorities, said Mr Thong.

Once the banks receive an order from the authorities, they can then freeze bank accounts, with the financial institutions also adopting a proactive approach.

OCBC, for instance, works closely with the police, with a team from the bank permanently stationed on-site at the police’s Anti-Scam Centre.

This way, fraudulent transactions are flagged more quickly, and then get blocked swiftly, said Mr Beaver Chua, head of anti-fraud at OCBC’s group financial crime compliance department.

Five other banks also have employees stationed there, including UOB and DBS.

UOB declined to provide details, citing operational sensitivities.

DBS Bank said it set up a separate anti-mule team in September, with the aim of tackling the problem at its source.

The head of the team, Mr Chris Huang, said it adopts a “pre-emptive approach of identifying and removing bad actors from the ecosystem even before they strike”.

The team comprises investigative specialists who specialise in “hunting down and eradicating money mules”.

In its second month, it worked alongside the police in an islandwide operation against money mules, resulting in the arrest of four men and one woman for their suspected involvement in scam cases.

More than $680,000 was seized during the course of the week-long operation.

In identifying potential money mules, Mr Huang said his team looks out for a few red flags, including unusual transaction patterns and withdrawals that do not measure up with the customer’s profile.

For instance, when someone without a high income makes a series of high-value deposits and withdrawals several days in a row, it will set off warning bells.

So why do people want to sign on for such a risky job? “The lure of quick cash is definitely one of the biggest reasons,” said Mr Huang.

“Some also have the misconception that if they are not directly involved in the crimes that generate the money, they are not committing an offence. However, it is illegal to sell accounts to criminals for fast cash,” he added.