SINGAPORE – New regulations for sea-based fish farms could be on the cards to ensure that aquaculture activities do not compromise the marine environment and the Republic’s limited sea space.

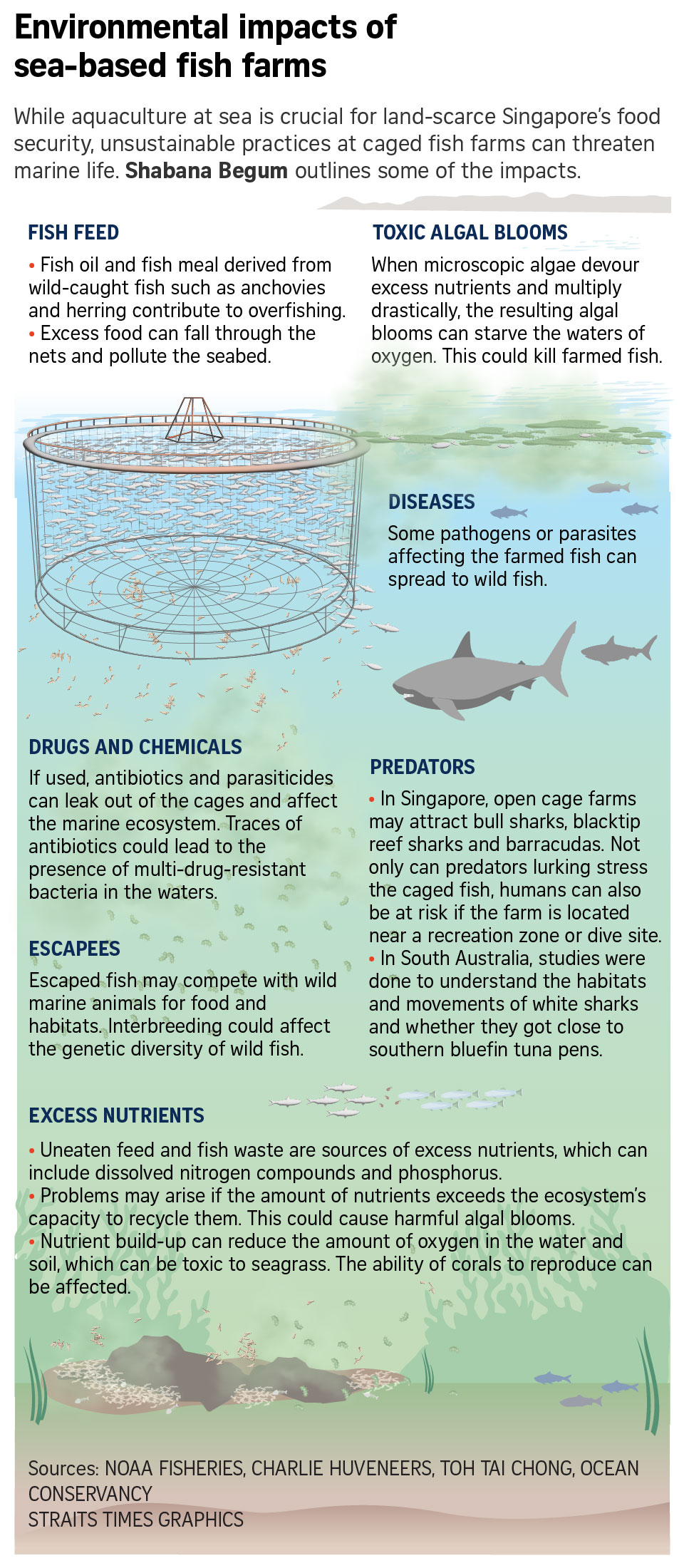

For example, open-net cage farms – which make up the majority of the aquaculture players here – may need to adopt more sustainable feeding and fish stocking practices, so that excess nutrients from the farms do not impact marine life or cause harmful algal blooms, said Senior Minister of State for Sustainability and the Environment Koh Poh Koon in June.

He added that the regulations, if introduced, would be shaped as “enabling legislations” to guide the industry to develop itself sustainably as it contributes to Singapore’s aim of producing 30 per cent of its nutritional needs by 2030.

This was one of the key takeaways from a five-day trip to Australia, where officials from the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) and the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment, as well as fish farmers and academics, sought to learn from the more advanced aquaculture sectors in Adelaide and Perth.

A main aim behind the trip from June 26 to 30 was to find ways to balance fish farm productivity with marine and environmental conservation.

Dr Koh said the laws, if passed, would likely be part of the upcoming Bill for Food Safety and Security, which was announced in Parliament in 2021.

“It is a Bill that will encompass all aspects of food security and safety, and clearly growing our fish sustainably is one of the food security measures that we want to implement,” he said.

He did not say when the Bill will be tabled.

In 2022, the 4,400 tonnes of seafood from local aquaculture production made up about 7.6 per cent of total seafood consumed here.

Since 2020, the authorities have been eyeing the Singapore Strait as yielding potential sites for aquaculture. Barramundi Asia is the only deep-sea fish farm in the southern waters, occupying three sites. The remainder of more than 100 offshore farms are along the Johor Strait.

In May 2022, marine biologists and nature groups reacted strongly when an environmental impact assessment identified the southern waters around the biodiversity-rich Pulau Satumu (where Raffles Lighthouse stands), Pulau Jong and Pulau Bukom as possible spaces to set up fish farms. They were worried about how the farms might affect marine life such as the endangered giant clam and coral reefs.

In June, the SFA said the tenders for two farm sites near Pulau Satumu and Pulau Jong would be postponed until further studies are done, while the tender for a site off Pulau Bukom will proceed, possibly in late 2023. But the site will be for a closed containment aquaculture system, which is believed to be less pollutive than open-net cage farms.

In Western Australia, considering fish farming’s toll on the environment is not an afterthought. Applicants for an aquaculture licence must submit an environmental management and monitoring plan to outline how risks to marine fauna and public safety will be managed.

Mr Steve Nel, aquaculture manager at the region’s Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, said: “We won’t grant an aquaculture licence until we are very clear that the (licensee) understands the requirements, what’s needed of them and the fact that we will be checking up on them through compliance... They also recognise that with a poor environment, their profit margins would go down.”

Dr Koh pointed out that Australia’s marine space is larger, with stronger currents to flush away waste and nutrient build-up at farming sites. Some farms also have the space to relocate their deep sea cages to allow their original sites and seabed to recover.

Aquaculture in Singapore’s waters

Singapore’s sea space, however, is much smaller and users include those from maritime and shipping, recreation, aquaculture and nature conservation, among others.

Along the Johor Strait, where almost all of the country’s offshore farms are located, flushing is limited, and the water is rich in nutrients and lower in oxygen. The narrow body of water is sheltered from oceanic currents. The Johor River also empties into the strait.

In 2015, 77 farms in Singapore were hit by an algal bloom that gobbled up oxygen from the water and wiped out more than 500 tonnes of fish, costing farms millions of dollars.

Dr Koh said the majority of fish farms here are traditional and subsistence-based. Farms that are more productive and technology-driven, which contribute to the bulk of the nation’s aquaculture, are in the minority.

The mortality rates for some traditional farms can be up to 70 per cent, and the fish are often fed with expired bread and confectionery, instead of protein-rich pellets.

“Some put chocolate inside the water to feed the fish as well... These methods of feeding end up polluting the water with unnecessary inorganic nutrients,” he added.

Over the next seven years, many of these farms could cease to exist, if owners were to retire or have no succession plans. But those who want to continue can get support from the SFA, which provides training or grants for technology adoption where eligible, Dr Koh said.

In the Singapore Strait, sites identified for aquaculture, or greenfield sites, will undergo more environmental impact assessments and collaborations with nature groups and academics.

National University of Singapore marine biologist Toh Tai Chong, who was part of the delegation to visit Australia, said: “Singapore’s small sea space means that a lot of key habitats like mangroves, seagrass and coral reefs are interconnected. When planning for our sea space... we need to avoid planning within individual segments to consider broader impacts on adjacent habitats.”

The country is looking, for instance, to restore reefs by planting 100,000 corals from 2024. Fish farms could also attract predators like bull sharks, and if a farm is close to a dive site, humans could be in danger.

Neither nature nor farming would win if the limited body of water cannot sustain its uses, noted Dr Koh.

A budget on nutrients

The Australia visit also introduced the delegation to the concept of a nutrient budget, which determines how much fish can be reared in an aquaculture zone.

If excess feed discharges more nutrients into the water, that would reduce the amount of fish that can be farmed, as farms also release nitrogen compounds and phosphorus through fish waste.

And in the Johor Strait where farms are in close proximity, one farm’s nutrient overload could affect another’s yield, said Dr Koh.

The SFA will study this concept further to see how it can be applied to Singapore.

Monitoring and modelling

In 2018, a fatal virus called Pacific Oyster Mortality Syndrome was detected in wild oysters in Adelaide’s Port River. The outbreak caused worry because the oyster farming industry was 60km from where the diseased shellfish were found.

Fortunately, computer modelling work done by researchers from the South Australian Research and Development Institute predicted that the pathogens would travel only up to 10km. The oyster farms were safe.

Separately, the University of Western Australia operates yellow rocket-like gliders in the waters around the Australian continent. Each unmanned vehicle can descend to 1,000m, picking up data such as the ocean’s temperature, salinity and dissolved organic matter.

The observations are recorded in the Australian Ocean Data Network, which stores a slew of marine and climate data.

Seawater monitoring in Singapore is not as extensive as that in Australia, noted Dr Koh, but oxygen levels in the Johor Strait are tracked and farmers are alerted if levels drop.

The aim moving forward is to develop a more comprehensive monitoring regime to better understand the health of the waters and guide fish farms.

This could involve working with technical agencies and researchers. The multi-institutional Marine Environment Sensing Network project, for instance, is looking to deploy three buoys off Singapore’s coast by 2025 to track more than 30 marine parameters including nutrients and oil pollution. The first buoy was installed off St John’s Island in late 2022.

The network is also testing nutrient sensors that might be suitable for Singapore’s waters.

Mr Malcolm Ong, chief executive of The Fish Farmer, which runs four farms off Lim Chu Kang and Changi, said: “Comprehensive monitoring will provide an accurate picture of what’s happening in our waters. Our sea has many uses. It can’t only be farms causing (water quality) problems.”