President Barack Obama had a China problem. His national security team knew the Chinese Communist Party was getting ready to anoint a new leader. But his aides wanted to better understand the man they expected to assume power, Mr Xi Jinping. It seemed like a job for Vice-President Joe Biden.

Mr Xi was China's Vice-President then, Mr Biden's US counterpart and natural interlocutor. Beyond that, Mr Obama and his aides hoped Mr Biden's ingratiating charm and decades of interactions with foreign leaders might allow him to penetrate Mr Xi's officially scripted facade. Starting in early 2011 and over the next 18 months, the two men convened at least eight times, in the United States and China, according to former US officials.

They met formally, took walks, shot baskets at a Chinese school and spent over 25 hours dining privately, joined only by interpreters. Mr Biden made a quick "personal connection" with the Chinese leader, even if he sometimes confounded his Mandarin interpreter by quoting hard-to-translate Irish verse, said Mr Daniel Russel, an aide present at several meetings.

"He was remarkably good in getting to a personal relationship right away and getting Xi to open up," Mr Russel said. Mr Biden's gleaned insights - especially his assessment of Mr Xi's authoritarian intentions - informed Mr Obama's later approach, several of the president's aides said in interviews.

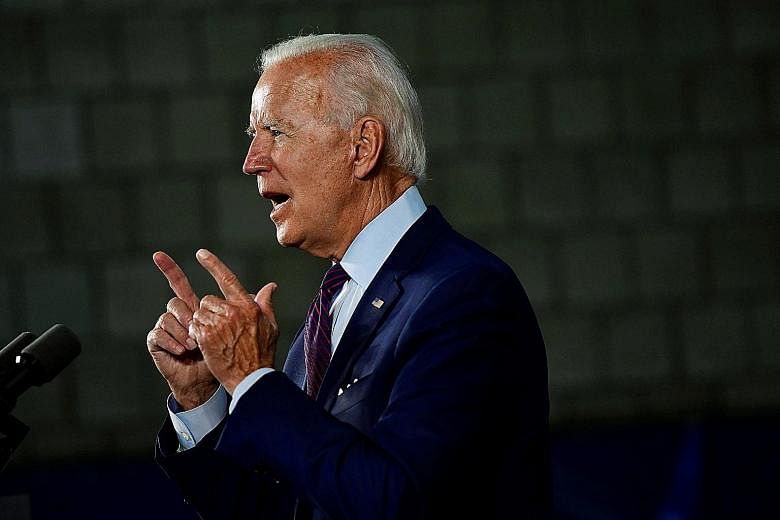

To voters unsettled by President Donald Trump's disruptive approach to the world, Mr Biden is selling not only his policy prescriptions but also his long track record of befriending, cajoling and sometimes confronting foreign leaders - what he might call the power of his informal diplomatic style. "I've dealt with every one of the major world leaders that are out there right now, and they know me. I know them," he told supporters in December.

Mr Brett McGurk, a former State Department official for the campaign against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), said Mr Biden was an effective diplomat by practising "strategic empathy". He is a foreign-policy pragmatist, not an ideologue; his views have long tracked the Democratic mainstream. For a decade before the Iraq War, he was known as a hawk, but has since been a chastened sceptic of foreign intervention.

In lieu of grand strategy, he offers what more than 20 current and former US officials describe as a remarkably personal diplomacy derived from his decades in the glad-handing, deal-making hothouse of the Senate. It is an approach grounded in a belief that understanding another leader - "what they want and what they need", in the words of former Biden aide James Rubin - is as important as understanding his or her nation.

"It's very Lyndon Johnson-esque," said Mr Husain Haqqani, a former Pakistani ambassador to Washington who attended many meetings with Mr Biden.

Yet Mr Xi has clearly tested the limits of that approach. Mr Biden's record is short on public warnings that the Chinese leader could become the "thug" that the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee calls him today. And as US ties with China slide from bad to worse, Mr Biden is facing uncomfortable questions about why he did not do more to stiffen Obama administration policy towards Beijing - about why his strategic empathy did not come with more strategic vision.

That is a point the Trump campaign seeks to make by weaponising Mr Biden's diplomatic dance with Mr Xi. A series of Trump campaign ads shows Mr Biden and Mr Xi clinking glasses against an audio backdrop of Mr Biden waxing lyrical about friendship and cooperation with China. The Biden campaign calls such criticism preposterous from a President who has himself repeatedly praised Mr Xi as a friend and a "great leader". But the attack is part of a broader Trump indictment of Mr Biden as "China's puppet" - a Washington establishment fixture who misread China and Mr Xi.

Mr Biden's critics insist his emphasis on the personal is not effective at all, that it covers for flawed judgment and a lack of principle. "It's little wonder he claims world leaders have told him they support his election - they want to get back to eating America's lunch again," said Mr Tim Murtaugh, a Trump campaign spokesman. He pointed out that Mr Biden had voted to authorise the Iraq War and said he favoured "appeasing" Cuba.

The effectiveness of Mr Biden's diplomatic style - and how well it might translate to the presidency - is hard to measure. As a senator, he produced no landmark foreign-policy legislation or defining doctrines. As vice-president, he was largely a facilitator and adviser to Mr Obama, often overshadowed by the secretaries of state Hillary Clinton and John Kerry.

Asked in an interview to cite instances where his approach to diplomacy proved successful, Mr Biden pointed to his work wrangling global support for the Paris climate accords and for the coalition to fight ISIS, though those were both projects in which others, including Mr Kerry, played major roles.

"I can't think of any place, to be honest with you, that it didn't work," he said. "For example," he continued, before pausing. "Well, I could give one example, but I don't think it helps me - especially if I get elected, with that particular leader still around."

WILMINGTON TO MOSCOW

Soon after his January 2001 inauguration, President George W. Bush invited Mr Biden to the Oval Office. A foreign-policy novice, Mr Bush was seeking insights into world leaders he was soon to meet. Mr Biden later wrote that the new Republican president "had all these other policy people to talk to, but he wanted to talk with another politician who had sat down with these leaders, who maybe had a read on the personalities and the motivations".

Mr Biden's political trademark was a blue-collar Everyman style that seemed more suited for state fairs than state dinners. But from the start of his Washington career, he had prioritised foreign policy - albeit preferring personal relationships to the book smarts of seasoned diplomats who sometimes rolled their eyes at him. "There's an old Chinese saying, better to travel 10,000 miles than read 10,000 books," Mr Biden likes to say.

In 1979, Mr Biden, aged 37, met China's leader Deng Xiaoping in Beijing, and later recalled the value of seeing firsthand Mr Deng's "very real fear of the Soviets". The same year he visited Moscow for nuclear arms talks with Kremlin officials including Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. After a senior official was evasive about Soviet tank numbers, Mr Biden offered a vulgar retort that a translator later diluted to: "Don't kid a kidder."

By his first run for president in 1988, Mr Biden considered himself an expert diplomat. "I knew the world and America's place in it in a way few politicians did," he wrote in a memoir. He marvelled at the "personal intimacy of diplomacy". After he withdrew from that campaign, he used his growing seniority on the Foreign Relations Committee to raise his profile on global issues. He would oppose the 1991 war to expel Iraq from Kuwait, but a few years later, he was among the few voices urging then President Bill Clinton to take military action in the Balkans.

Mr Biden's thinking was shaped in part by an encounter with Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic. During an April 1993 meeting in Belgrade, Mr Biden has recalled, he told Milosevic: "I think you're a damn war criminal and you should be tried as one." (Whether Mr Biden uttered those exact words has been disputed, although Mr Rubin, who was present, called the encounter "the most intense grilling I ever saw an American give to a foreign leader".) He came away convinced that Milosevic was "evil", he later wrote, and that the US should bomb Serbian forces.

When Mr Obama chose Mr Biden as his 2008 running mate - in part for the foreign-policy experience that Mr Obama lacked - it formed a glaring contrast with Mr Biden's Republican rival, Ms Sarah Palin. To drive home the point, Mr Biden's office released a "partial" list of nearly 150 leaders from some 60 countries whom he had met over his career - including nine Israeli premiers, six Russian leaders, five German chancellors, along with Queen Elizabeth II, Bashar Assad, Vaclav Havel and Nelson Mandela.

Mr Obama had overlooked his running mate's 2002 Iraq War vote, which Mr Biden - then a leading Democratic advocate of a muscular US foreign policy - now says he regrets. Looking forward, the new president tasked Mr Biden with overseeing post-war Iraq, telling aides: "He knows the players."

'BLUNT WITHOUT BEING RUDE'

As his long-ago encounter with Milosevic shows, Mr Biden can also do confrontation.

That was showcased, a bit uncomfortably, during the Trump impeachment. In 2015, Mr Biden had browbeaten Ukraine's leaders to fire a corrupt federal prosecutor as a condition for a US$1 billion (S$1.4 billion) loan guarantee from the US. "I looked at them and said: 'I'm leaving in six hours. If the prosecutor is not fired, you're not getting the money'," Mr Biden said in a 2018 public appearance. Mr Trump seized on the remarks to suggest, without evidence, that Mr Biden had acted improperly.

Mr Biden relishes such stories: He often recalls a 2009 meeting in Moscow with then Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, in which Mr Biden says he placed a hand on the Russian leader's shoulder and said: "Mr Prime Minister, I'm looking into your eyes. I don't think you have a soul." Or the 2004 meeting in Libya with dictator Muammar Gaddafi ("the strangest bird I think I've dealt with," he recalls), whom he called a "terrorist" to his face.

Mr Haqqani recalled a 2009 meeting in Islamabad at which Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari suggested that the US would abandon Afghanistan because its people were afraid to fight there. The comment sent Mr Biden "into a moderate rage", Mr Haqqani said. "Don't you think we are ever frightened!" he snapped. Mr Zardari was impressed, but not offended, according to Mr Haqqani.

Mr Biden "can be blunt without being rude, which in diplomacy is a great asset", said Mr Haqqani, now a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, a conservative US think-tank.

But Mr Michael Doran, a national security aide in Mr Bush's White House now also at the Hudson Institute, argued that many foreign leaders see Mr Biden, who he said had offended allies with his infamous gaffes, as unreliable.

"The claim that Biden's relationships and experience are an asset has been a part of his standard rhetoric for years, but they mean nothing if people don't trust him," Mr Doran said.

A NEW VIEW OF XI

Mr Biden said he was impressed during his meetings with Mr Xi, who became China's President in 2013. "He's a smart guy," Mr Biden said. "He would ask very revealing questions." Mr Xi asked about how the US political system works, the power of governors, and how much authority the American president wields over the military and intelligence agencies, Mr Biden said. "So my conclusion was he was very much trying to do something that no one had ever done since Deng Xiaoping, and that is to actually control the government, not just the party," he said. Mr Xi has since emerged as a stern authoritarian.

During their initial courtship, Mr Biden praised Mr Xi as a friend who impressed him with "openness and candour". Today, with the Chinese leader's global reputation souring and Mr Trump applying political pressure, Mr Biden speaks of him in more critical terms.

Mr Biden was scathing during a Democratic debate, saying of Mr Xi: "This is a guy who is - doesn't have a democratic, with a small D, bone in his body. This is a guy who is a thug, who in fact has a million Uighurs in 'reconstruction camps', meaning concentration camps."

Still, asked in the interview how he now viewed Mr Xi, Mr Biden seemed to be walking a diplomatic tightrope. At first, he reverted to personal anecdotes, recalling how he had told Mr Xi in 2013 that the US would fly bombers "right through" a military air zone China had declared over disputed Pacific waters. And with a flourish of machismo, he recounted his answer when Mr Xi asked why Obama officials kept referring to the US as a "Pacific power", a term some in China consider an affront.

"Because we are," Mr Biden said he replied.

"And he looked at me and said: 'Yeah.' Just stared. 'You got that right'," Mr Biden said.

Mr Biden also suggested in the interview that Mr Xi bore significant blame for China's secretive initial response to the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan in January, which many experts say cost the world valuable time. "It didn't surprise me at all," Mr Biden said.

All of which might portend a hostile relationship between the men. Except Mr Biden declined to go further. "God willing, I may have to deal with him," he said, "and I don't want to burn all of my bridges here."

NYTIMES